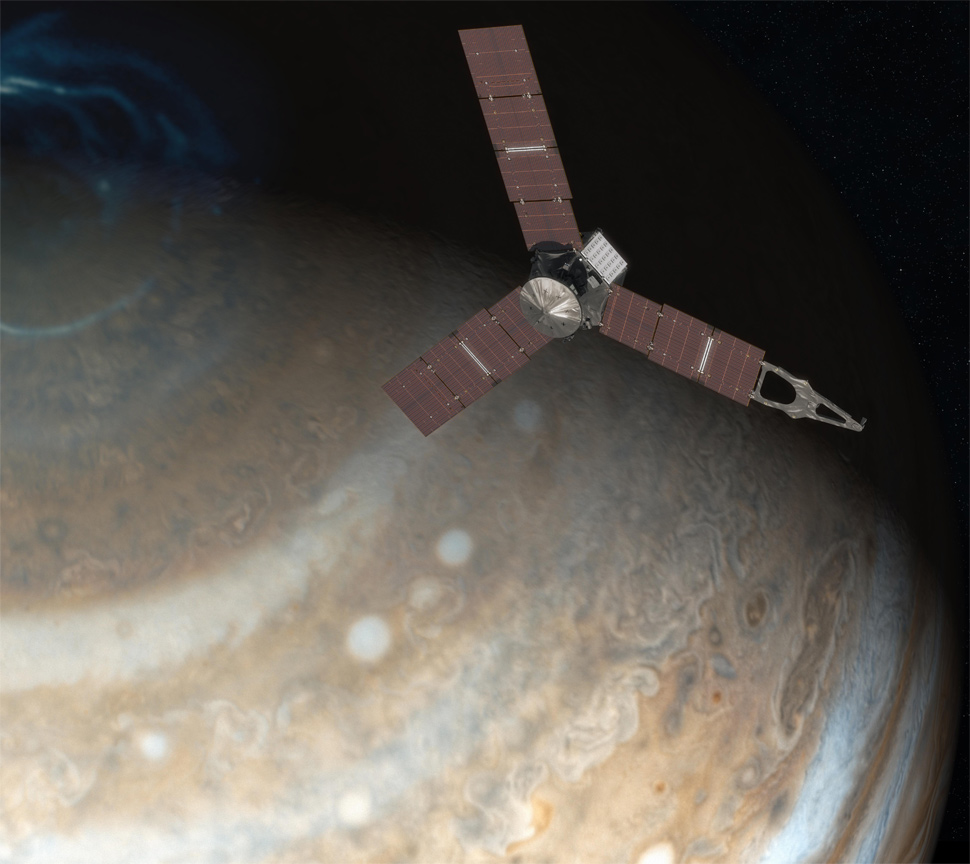

5th July 2016 NASA's Juno spacecraft enters orbit around Jupiter After a five-year journey to the Solar System's largest planet, NASA's Juno probe has successfully entered Jupiter's orbit during a 35-minute engine burn. Confirmation that the burn had completed was received on Earth at 8:53 p.m. PDT (11:53 p.m. EDT) on Monday 4th July.

"Independence Day always is something to celebrate, but today we can add to America's birthday another reason to cheer – Juno is at Jupiter," said NASA administrator Charlie Bolden. "And what is more American than a NASA mission going boldly where no spacecraft has gone before? With Juno, we will investigate the unknowns of Jupiter's massive radiation belts to delve deep into not only the planet's interior, but into how Jupiter was born and how our entire Solar System evolved." Confirmation of a successful orbit insertion was received from Juno tracking data monitored at the navigation facility at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, as well as at the Lockheed Martin Juno operations centre in Littleton, Colorado. The telemetry and tracking data were received by NASA's Deep Space Network antennas in Goldstone, California, and Canberra, Australia. "This is the one time I don't mind being stuck in a windowless room on the night of the 4th of July," said Scott Bolton, principal investigator of Juno from Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. "The mission team did great. The spacecraft did great. We are looking great. It's a great day." Preplanned events leading up to the orbital insertion engine burn included changing the spacecraft's attitude to point the main engine in the desired direction and then increasing the spacecraft's rotation rate from two to five revolutions per minute (RPM) to help stabilise it. The burn of Juno's 645-Newton Leros-1b main engine began on schedule at 8:18 p.m. PDT (11:18 p.m. EDT), decreasing the spacecraft's velocity by 1,212 mph (542 metres per second) and allowing Juno to be captured in orbit around the gas giant. Soon after the burn was completed, Juno turned so that the Sun's rays could once again reach the 18,698 individual solar cells that give Juno its energy.

"The spacecraft worked perfectly, which is always nice when you're driving a vehicle with 1.7 billion miles on the odometer," said Rick Nybakken, Juno project manager from JPL. "Jupiter orbit insertion was a big step and the most challenging remaining in our mission plan, but there are others that have to occur before we can give the science team the mission they are looking for." Over the next few months, Juno's mission and science teams will perform final testing on the spacecraft's subsystems, final calibration of science instruments and some science collection. "Our official science collection phase begins in October, but we've figured out a way to collect data a lot earlier than that," said Bolton. "Which when you're talking about the single biggest planetary body in the Solar System is a really good thing. There is a lot to see and do here." Juno's principal goal is to understand the origin and evolution of Jupiter. With its suite of nine science instruments, Juno will investigate the existence of a solid planetary core, map Jupiter's intense magnetic field, measure the amount of water and ammonia in the deep atmosphere, and observe the planet's auroras. At its closest approach, it will come within 3,000 miles (5,000 kilometres) of the cloud tops. The mission will take a major step forward in our understanding of how giant planets form and the role these titans played in putting together the rest of the Solar System. As our primary example of a giant planet, Jupiter can also provide critical knowledge for understanding the planetary systems being discovered around other stars. ---

Comments »

|