15th December 2017 NASA uses AI to find hidden exoplanets NASA astronomers have announced the detection of Kepler-90i, a super-Earth exoplanet, and the eighth in a multi-exoplanetary system orbiting the star Kepler-90, which now hosts the most exoplanets ever found to date orbiting an extrasolar star. The exoplanet was found in archival data gathered by the Kepler space telescope with the aid of a newly utilised computer tool, deep learning, a class of machine learning algorithms.

Our Solar System is now tied for the most number of planets around a single star, with the recent discovery of an eighth planet orbiting Kepler-90, a G-type (Sun-like) star 2,545 light-years from Earth. The planet was found in data from NASA's Kepler Space Telescope. The newly-discovered Kepler-90i – a hot, rocky planet orbiting its star every 14.4 days – was found using machine learning from Google. Machine learning is an approach to artificial intelligence in which computers "learn." In this case, computers learned to identify planets by finding instances in Kepler data where the telescope recorded signals from planets beyond our Solar System, known as exoplanets. Two researchers, Christopher Shallue and Andrew Vanderburg, trained a computer to identify exoplanets in the light readings of Kepler – the minuscule changes in brightness captured when a planet passed in front of, or transited, a star. Inspired by the way neurons connect in the human brain, this AI "neural network" sorted through Kepler data and found weak transit signals from a previously-missed eighth planet orbiting Kepler-90. "Just as we expected, there are exciting discoveries lurking in our archived Kepler data, waiting for the right tool or technology to unearth them," said Paul Hertz, director of NASA's Astrophysics Division in Washington, D.C. "This finding shows that our data will be a treasure trove available to innovative researchers for years to come."

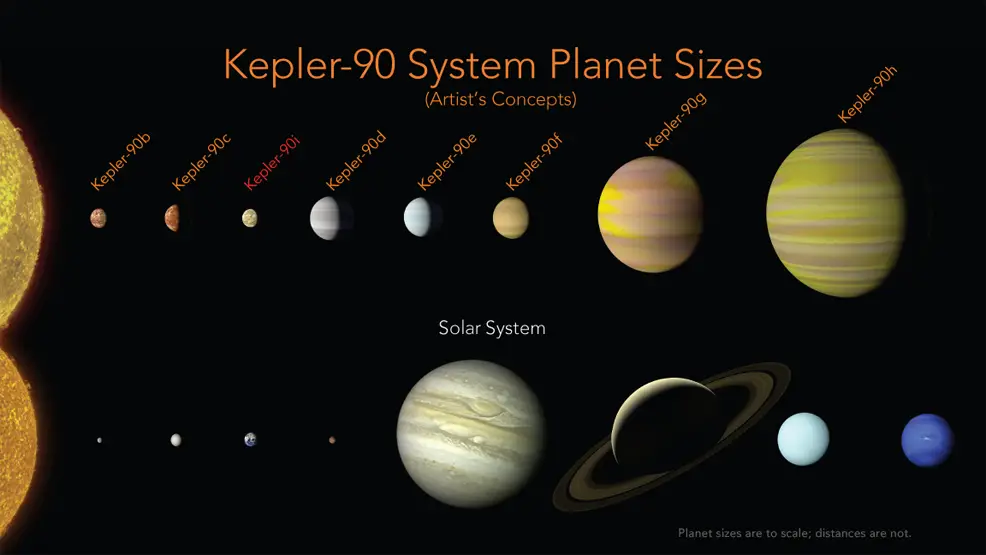

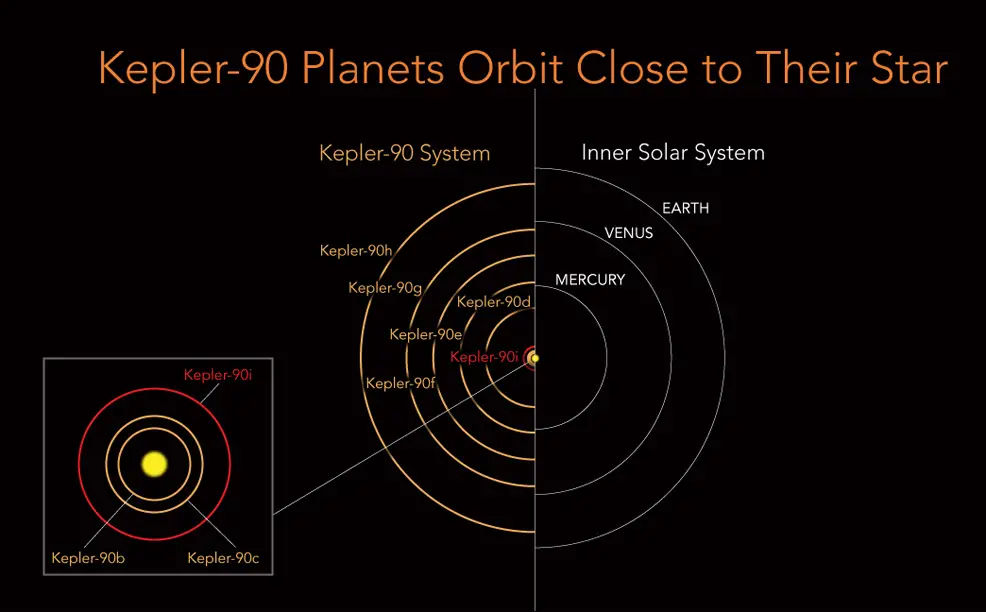

In terms of alien life, other planetary systems probably hold more promise than Kepler-90. About 30% larger than Earth, Kepler-90i is so close to its star that its average surface temperature is believed to exceed 800 degrees Fahrenheit, on a par with Mercury. Its outermost planet, Kepler-90h, orbits at a similar distance to its star as Earth does to the Sun. "The Kepler-90 star system is like a mini version of our solar system," said Vanderburg, a NASA Sagan Postdoctoral Fellow and astronomer at the University of Texas at Austin. "You have small planets inside and big planets outside, but everything is scrunched in much closer."

Shallue, a senior software engineer with Google's AI research team, came up with the idea to apply a neural network to Kepler data. He became interested in exoplanet discovery after learning that astronomy, like other branches of science, is being rapidly inundated with data as the technology for data collection from space advances. "In my spare time, I started googling for 'finding exoplanets with large data sets' and found out about the Kepler mission and the huge data set available," said Shallue. "Machine learning really shines in situations where there is so much data that humans can't search it for themselves." Kepler's four-year dataset consists of 35,000 possible planetary signals. Automated tests, and sometimes human eyes, are used to verify the most promising signals in the data. However, the weakest signals are often missed using these methods. Shallue and Vanderburg thought there could be more interesting exoplanet discoveries faintly lurking in the data. First, they trained the neural network to identify transiting exoplanets using a set of 15,000 previously-vetted signals from the Kepler exoplanet catalogue. In the test set, the neural network correctly identified true planets and false positives 96 percent of the time. Then, with the neural network having "learned" to detect the pattern of a transiting exoplanet, the researchers directed their model to search for weaker signals in 670 star systems that already had multiple known planets. Their assumption was that multiple-planet systems would be the best places to look for more exoplanets. "We got lots of false positives of planets, but also potentially more real planets," said Vanderburg. "It's like sifting through rocks to find jewels. If you have a finer sieve then you will catch more rocks – but you might catch more jewels, as well." Kepler-90i wasn't the only jewel this neural network sifted out. In the Kepler-80 system, they found a sixth planet. This one, the Earth-sized Kepler-80g, and four of its neighbouring planets form what is called a "resonant chain" – where planets are locked by their mutual gravity in a rhythmic orbital dance. The result is an extremely stable system, similar to the seven planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system. "These results demonstrate the enduring value of Kepler's mission," said Jessie Dotson, Kepler's project scientist at NASA's Ames Research Center in California's Silicon Valley. "New ways of looking at the data – such as this early-stage research to apply machine learning algorithms – promises to continue to yield significant advances in our understanding of planetary systems around other stars. I'm sure there are more firsts in the data waiting for people to find them." A research paper describing these findings has been accepted for publication in The Astronomical Journal. Shallue and Vanderburg plan to apply their neural network to Kepler's full set of more than 150,000 stars.

Comments »

If you enjoyed this article, please consider sharing it:

|