30th December 2019 North Atlantic Current may cease temporarily in the next century The North Atlantic Current transports warm water from the Gulf of Mexico towards Europe – providing much of north-western Europe with a relatively mild climate. Scientists predict a small, but not insignificant (15%) chance of a temporary halt to the current in the next 100 years due to climate change.

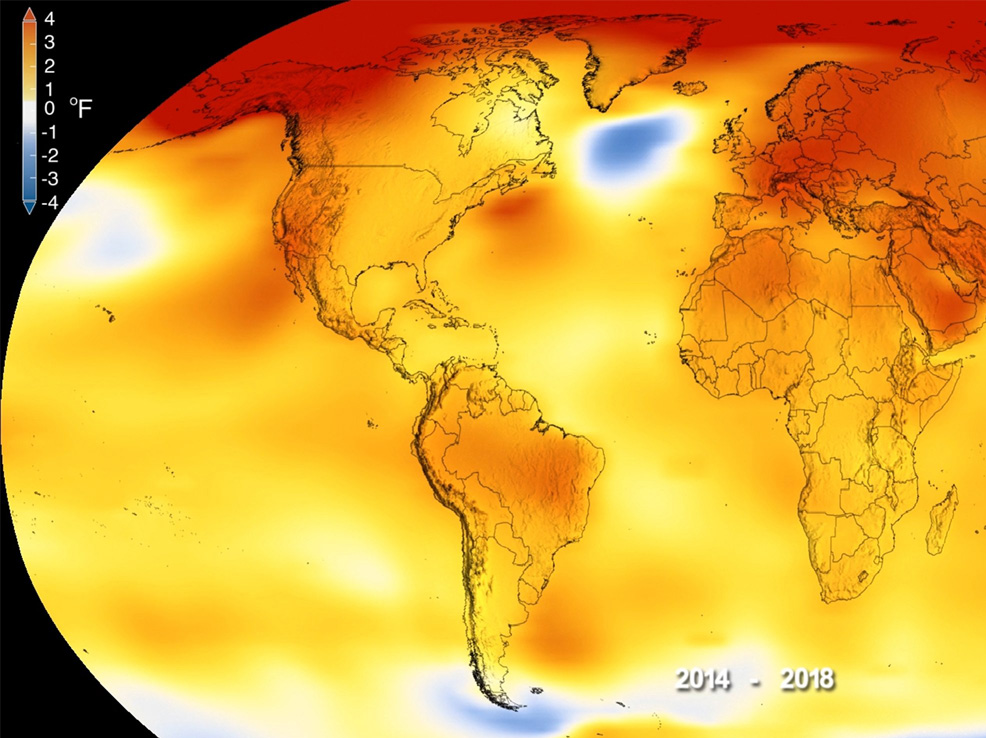

In recent years, increasing numbers of scientists have begun to suspect that meltwater from Greenland, combined with excessive rainfall, could interfere with the North Atlantic Current. Extending from the Gulf Stream, this brings more tropical water to northern latitudes than any other boundary current and provides up to 5°C (9°F) in additional warmth for countries like Ireland and the United Kingdom. Disruption to this "conveyor belt" of heat, therefore, could have serious implications for Europe's weather and a knock-on effect on the global climate. Indeed, it was the subject of The Day After Tomorrow, a 2004 science fiction movie in which the world experiences the beginnings of a new ice age. New simulations, produced by scientists from the University of Groningen and Utrecht University, show it is unlikely that the North Atlantic Current will come to a complete stop, due to small and rapid changes in precipitation over the North Atlantic. However, there is a 15% likelihood of a temporary change in the current during the next 100 years. The results are published today in the journal Scientific Reports. "The oceans store an immense amount of energy and the ocean currents have a strong effect on the Earth's climate," says Fred Wubs, Associate Professor in Numerical Mathematics at the University of Groningen. Together with his colleague, Henk Dijkstra, from Utrecht University, he has studied ocean currents for some 20 years. Ocean scientists know that the Atlantic Ocean currents are sensitive to the amount of fresh water at the surface. Since the run-off of meltwater from Greenland has increased due to climate change, as has rainfall over the ocean, it has been suggested that this may slow down or even reverse the North Atlantic Current, blocking the transport of heat to Europe.

Simulations of the effects of freshwater on the currents have already been performed for some decades. "Both high-resolution models, based on the equations describing fluid flows, and highly simplified box models have been used," says Wubs. "Our colleagues in Utrecht created a box model that describes present-day large-scale processes in the ocean rather well." The idea was to use this box model to estimate the likelihood of small fluctuations in freshwater input causing a temporary slowing down or a total collapse of the North Atlantic Current. The current shows non-linear behaviour, which means that small changes can have large effects. The evolution of the physics described by the box model can only be obtained using simulations. "As the transitions we were looking for are expected to be rare events, you need a huge number of simulations to estimate the chance of them happening," explains Wubs. However, the Dutch scientists found that a French scientist had devised a method to select the most promising simulations, reducing the number of full simulations required. Sven Baars, a PhD student of Wubs, implemented this method and linked it to the Utrecht box model. The simulations were performed by a PhD student from Utrecht University, Daniele Castellana: "These showed that the chances of a total collapse of the North Atlantic Current in the next thousand years are negligible," explains Wubs. A more likely scenario is the temporary blockage of warm water delivery to north-western Europe. "In our simulations, the chances of this happening within the next 100 years are 15%." For north-western Europe, this event may cause intense cold conditions – although the extent of those changes, and the mechanisms involved in the transition, need to be verified in further research. Therefore, the current study is just a first step in determining the risk. Confirming the results through simulation with a higher-resolution climate model will be the next challenge, concludes Wubs.

Comments »

If you enjoyed this article, please consider sharing it:

|