15th December 2020 Thymus built from human stem cells A human thymus rebuilt using stem cells and a bioengineered scaffold has been demonstrated by researchers at the Francis Crick Institute and University College London.

Researchers from the Francis Crick Institute (FCI) and University College London (UCL) have rebuilt a human thymus, an essential organ of the immune system, using human stem cells and a bioengineered scaffold. Their work is an important step towards being able to grow artificial thymi for use as transplants. The thymus – located in the upper front part of the chest, behind the sternum – is a lymphoid organ where T cells mature. These play a vital role in the body's immune system. If the thymus does not work properly or does not form during foetal development in the womb, it can result in severe immunodeficiency and other conditions where the body cannot fight infectious diseases or cancerous cells, or autoimmunity, where the immune system mistakenly attacks the patient's own healthy tissue. In their proof-of-concept study, published in Nature Communications, the scientists rebuilt thymi using stem cells taken from patients who had to have the organ removed during surgery. When transplanted into mice, the bioengineered thymi were able to support the development of mature and functional human T cells. While scientists have previously rebuilt other organs, or sections of organs, this is the first time they have successfully rebuilt a whole working human thymus. Funded by the European Research Council, this study is an important step not only for further research into and treatment of severe immune deficiencies but also more broadly for developing new techniques to grow artificial organs. "Showing it is possible to build a working thymus from human cells is a crucial step towards being able to grow thymi which could one day be used as transplants," said Sara Campinoti, author and researcher in the Epithelial Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine Laboratory at the FCI.

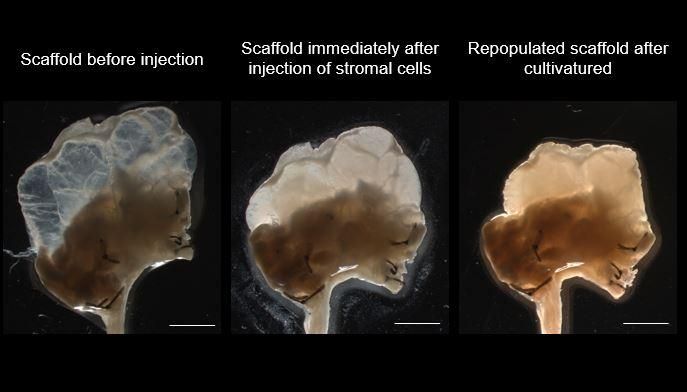

To rebuild this organ, the researchers collected thymi from patients and in the laboratory, grew thymic epithelial cells and thymic interstitial cells from the donated tissue into many colonies of billions of cells. For the next step, they obtained a structural scaffold of thymi, which they repopulated with the thymic cells they had cultured. This required the development of a new approach to remove all the cells from rat thymi, so only the structural scaffolds remained. They had to use a new microvascular surgical technique, as the conventional methods are not effective for a thymus. "This new approach is important because it enables us to obtain scaffolds from larger organs like the human thymus – something essential to bringing this beautiful work to the clinic," said Asllan Gjinovci, who developed the new method. The researchers then injected the organ scaffolds with up to six million human thymic epithelial cells, as well as interstitial cells from the colonies they had grown in the lab. The cells grew onto the scaffolds and after only five days, the organs had developed to a similar stage as those seen in nine-week-old foetuses. Finally, the team implanted these thymi into mice. They found that in over 75% of cases, the thymi were able to support the development of human lymphocytes. "The fact that we can extensively expand thymic stem cells taken from human donors into large colonies is really exciting. It makes it possible to scale up the process with a view to build 'human size' thymi," said Roberta Ragazzini, study co-author. "As well as providing a new source of transplants for people without a working thymus, our work has other potential future applications," said Paola Bonfanti, senior author and group leader at the FCI, and a professor in the Division of Infection and Immunity at UCL. "For example, as the thymus helps the immune system to recognise self from non-self, it poses a problem for organ transplants as it can cause the immune system to attack the transplant. "It is possible that we could overcome this by also transplanting a thymus regrown from cells taken from the thymus of the organ donor. We are confident that this may prevent the body attacking the transplant. The research behind this is still in early days, but it is an exciting concept which could remove the need for patients to take immune suppressors for the rest of their life." The researchers are continuing their work rebuilding thymi to refine and scale up the process.

--- Follow us: Twitter | Facebook | Instagram | YouTube

Comments »

If you enjoyed this article, please consider sharing it:

|