12th January 2023 Madagascar extinction recovery could take 23 million years The long-term impact of biodiversity loss in Madagascar has been modelled by researchers. Their work suggests that recovery from the current wave of extinctions could take as long as 23 million years.

Madagascar is one of the world's most biodiverse hotspots. Following the breakup of the prehistoric supercontinent of Gondwana, the island country split away from the Indian subcontinent about 80 million years ago, allowing native plants and animals to evolve in relative isolation. Consequently, over 90% of its wildlife is endemic and found nowhere else on Earth. But like other regions hosting many rare and beautiful species, Madagascar's rich ecosystems are fragile. In the modern era, its delicate balance of life has been threatened by catastrophic habitat loss, overhunting, and the impacts of a rapidly warming planet. Of its 219 known mammal species, for example, including 109 different lemurs, more than 120 are endangered. A new study – published this week in Nature Communications – examines how long it took Madagascar's unique species to emerge, and predicts how long it would take for a similarly complex set of new animals to evolve in their place, if the endangered ones went extinct: 23 million years, far longer than scientists have found for any other island. "It's abundantly clear – there are whole lineages of unique animals that only occur on Madagascar that have either gone extinct or are on the verge of extinction, and if immediate action isn't taken, Madagascar is going to lose 23 million years of evolutionary history. This means whole lineages unique to the face of the Earth will never exist again," explains Steve Goodman, a biologist at Chicago's Field Museum and one of the paper's authors. Madagascar is the world's fifth-largest island, about the size of France, but "in terms of all the different ecosystems present on Madagascar, it's less like an island and more like a mini-continent," says Goodman. In the 150 million years since Madagascar split from the African mainland and the 80 million since it parted ways with India, the plants and animals there have gone down their own evolutionary paths, cut off from the rest of the world. This smaller gene pool, coupled with Madagascar's wealth of different habitat types – from mountainous rainforests to lowland deserts – allowed animals there to split into different species far more quickly than their continental relatives.

But this incredible biodiversity comes at a cost: evolution happens faster on islands, but so does extinction. Smaller populations that are specially adapted to smaller, unique patches of habitat are more vulnerable to being wiped out, and once they're gone, they're gone. More than half of the mammals on Madagascar are included on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species, aka the IUCN Red List. These animals are endangered primarily because of human actions over the past 200 years, especially habitat destruction and over-hunting. For their study, Goodman and his colleagues built a dataset of every mammal species known to coexist with humans on the island for the last 2,500 years (humans have lived on Madagascar, perhaps intermittently, for 10,000 years, but have remained constant there for the last 2,500). About 12% of the 250 species went extinct over the past two millennia, including a gorilla-sized lemur that may have lived as recently as 500 years ago before disappearing. Using this dataset of all known mammals that interacted with humans, the researchers built genetic family trees to establish how all these species are related to each other and how long it took them to evolve from various common ancestors. Then, they extrapolated how long it took this amount of biodiversity to evolve, and thus, generated an estimate for how long it would take for evolution to "replace" all the endangered species if they go extinct. The damage already inflicted on Madagascar's ecosystems is substantial, but the impact from extinctions later this century may be staggering. To rebuild the diversity of land-dwelling mammals that disappeared over the past 2,500 years, it would take around 3 million years. But more alarmingly, the models suggest that if all mammals that are currently endangered also go extinct, it would take 23 million years to regain a similar level of evolutionary complexity. For comparison, the recovery time after the Permian–Triassic extinction event – the worst ever catastrophe for life on Earth – has an upper estimate of approximately 10 million years. "It is much longer than what previous studies have found on other islands, such as New Zealand or the Caribbean," says Luis Valente, study co-author and a biologist at the Naturalis Biodiversity Center and the University of Groningen in the Netherlands. "It was already known that Madagascar was a hotspot of biodiversity, but this new research puts into context just how valuable this diversity is. These findings underline the potential gains of the conservation of nature on Madagascar from a novel evolutionary perspective." According to Goodman, Madagascar is at a tipping point for protecting its biodiversity. "There is still a chance to fix things, but basically, we have about five years to really advance the conservation of Madagascar's forests and the organisms that those forests hold," he says. This urgent conservation work is made difficult by inequality and political corruption that keeps land-use decisions out of the hands of most Malagasy people, says Goodman: "Madagascar's biological crisis has nothing to do with biology. It has to do with socio-economics." But while the situation is dire, he says, "we can't throw in the towel. We're obliged to advance this cause as much as we can, and try to make the world understand that it's now or never."

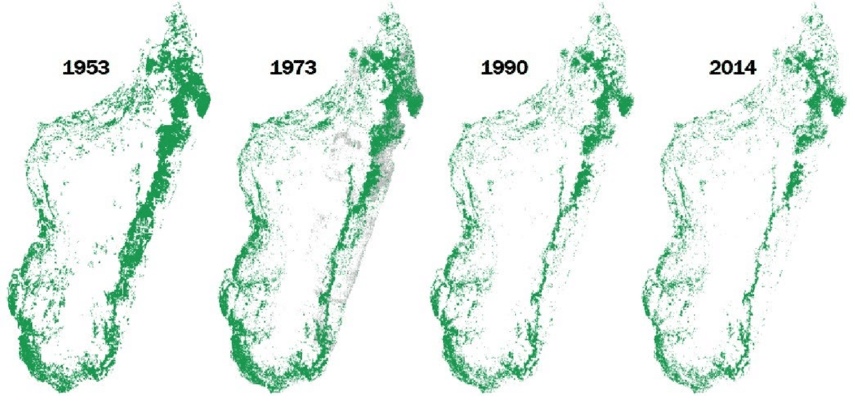

Tree cover on the island of Madagascar, 1953-2014. Credit: Ghislain Vieilledent, et al.

Comments »

If you enjoyed this article, please consider sharing it:

|