4th February 2023 Gene editing company plans to resurrect the dodo Colossal Biosciences, a genetic engineering company focused on de-extincting past species, has announced $150 million in Series B funding, which it plans to use for bringing back the iconic dodo.

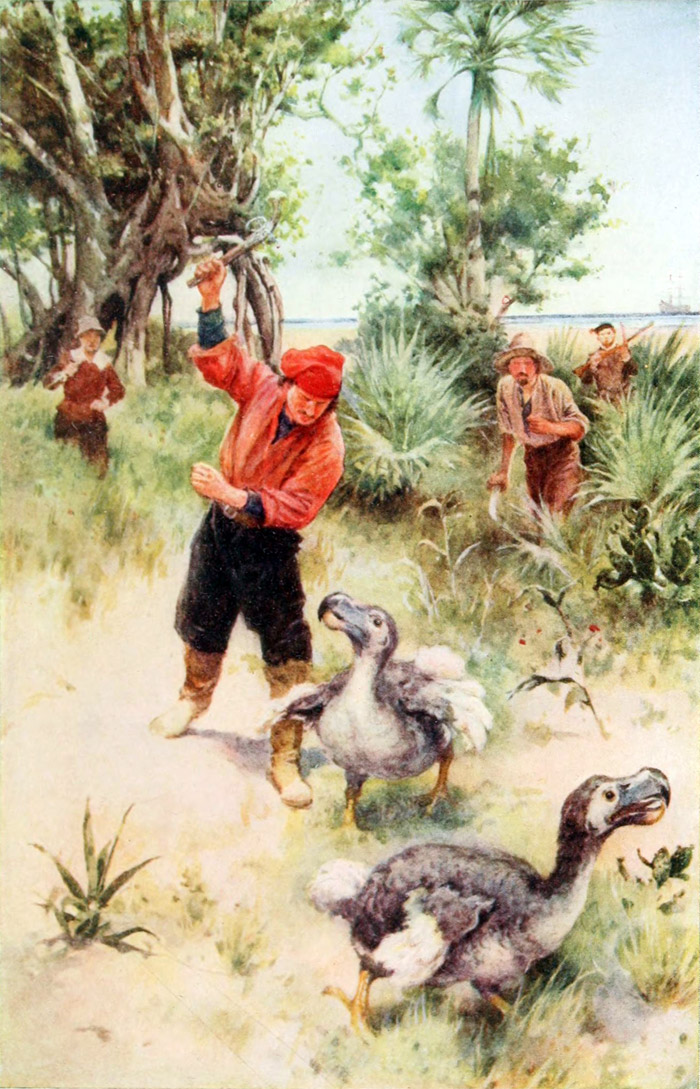

The resurrection of several extinct species is predicted to occur within the next five years. One company aiming to make that a reality is Texas-based startup Colossal Biosciences, founded in 2021 by some of the world's leading experts in genomics. In May 2022, it appeared in the World Economic Forum's list of Technology Pioneers and it won Genomics Innovation of the Year at the BioTech Breakthrough Awards. Colossal has already begun working to bring back a woolly mammoth. The huge, tusked animals co-existed with humans during the Stone Age, before entering a rapid decline from around 15,000 BC onwards. The last remaining animal is believed to have died on the Taymyr Peninsula of Siberia between 2100 and 1900 BC. Scientists first sequenced a complete genome of the woolly mammoth in 2015 and performed a detailed analysis of it that same year. Building on that research, Colossal aims to develop a proxy species by swapping key mammoth genes into an Asian elephant genome, which shares 99.6% of the same DNA. The first woolly mammoth hybrid calves are expected by 2027 and – if born alive and healthy – will be reintroduced to an Arctic habitat. Last year, the company revealed a second project: de-extinction of the thylacine, also known as the Tasmanian tiger. This carnivorous marsupial, noted for its distinctive striped appearance, roamed throughout Australasia for millions of years, before hunting by humans led to a population crash. The last known animal died at Hobart Zone in 1936. Tasmanian tigers could soon be making a reappearance, however, as Colossal's lead researcher, Andrew Pask, PhD, reports that his team's research is now "massively accelerated and currently ahead of our internal schedules." A third project is now underway – an attempt to resurrect the extinct Dodo – thanks to $150m in Series B financing announced this week. This latest round is led by United States Innovative Technology Fund (USIT), with many others participating, and brings the company's total funding to an impressive $225m. The dodo, a flightless bird, lived on the Indian Ocean island of Mauritius. It stood 1 metre (3 ft 3 in) tall and weighed up to 17.5 kg (39 lb). The first known historical records of the dodo are from Dutch sailors in 1598. Upon settling the island, they immediately began hunting the bird, while destroying its habitat and introducing many invasive species, including cats, dogs, monkeys, pigs, and rats. Like many animals that evolved in isolation from significant predators, the dodo did not fear humans. This fearlessness, and its inability to fly, made it easy prey for sailors.

Despite the human population of Mauritius never going above 50 during this time, the settlers had a major impact on the island and its ecosystems. In just a matter of decades, the dodo had gone extinct, with its last known widely accepted sighting in 1662. The loss of such a unique bird so soon after its discovery brought attention to the previously unrecognised problem of human involvement in the disappearance of entire species. Since then, it has become a fixture in popular culture, often as a symbol of extinction and obsolescence. But if Colossal Biosciences is successful, the old phrase "dead as a dodo" may start to fall out of use. The company will use its latest infusion of capital to fund a new Avian Genomics Group, not only to research ways of bringing the iconic dodo back, but potentially many other birds too. The IUCN Red List has categorised more than 400 bird species as either extinct, extinct in the wild, or critically endangered. DNA sequencing has shown that pigeons are related to the dodo, the closest known match being the Nicobar pigeon. Scientists at Colossal intend to work with pigeon eggs, and use genetic material that can be tweaked to mirror the dodo's key traits. Their research could help to improve genetic engineering and lead to revolutionary software, wetware, and hardware solutions, applicable to both conservation and human healthcare. "The Dodo is a prime example of a species that became extinct because we – people – made it impossible for them to survive in their native habitat," explained Beth Shapiro, PhD, a scientific advisory board member and lead paleogeneticist at Colossal. "Having focused on genetic advancements in ancient DNA for my entire career, and as the first to fully sequence the dodo's genome, I am thrilled to collaborate with Colossal and the people of Mauritius on the de-extinction and eventual re-wilding of the dodo. I particularly look forward to furthering genetic rescue tools focused on birds and avian conservation." "Methods for reading and writing DNA are helping make Earth a healthier place to live, medically and environmentally," said George Church, world-renowned geneticist and co-founder of Colossal. "Genetic technologies are already protecting us and our food sources from infectious and inherited diseases. A society embracing endangered and extinct gene variants is one poised to address many practical obstacles and opportunities in carbon sequestration, nutrition, and new materials. I am pleased with our company's progress across multiple vertebrate species." "Dr. George Church and Colossal's deep work in genomics is creating some of the most cutting-edge advancements in biotech. Their innovative technology has important applications for scientific discoveries, including biomedicine, and we look forward to supporting this crucial work," said Thomas Tull, Chairman of USIT, which led the latest funding round. Not everyone is enamoured with the idea of resurrecting extinct species, however. A number of people in the scientific community have expressed contrary views that may invite comparisons with Jurassic Park's famous dinner scene. "There is no doubt this is an iconic bird," said Prof Ewan Birney, deputy director of the European Molecular Biology Laboratory, who is not involved with Colossal. "I've no idea whether the mechanics of this will work as they claim, but the question is not just can you do this but should you do it. There are people who think that because you can do something you should; but I'm not sure what purpose it serves, and whether this is really the best allocation of resources. We should be saving the species that we have before they go extinct." "There's a real hazard in saying that if we destroy nature, we can just put it back together again – because we can't," said Duke University ecologist Stuart Pimm, who has no connection to Colossal. "And where on Earth would you put a woolly mammoth, other than in a cage?" "Preventing species from going extinct in the first place should be our priority, and in most cases, it's a lot cheaper," said Boris Worm, a biologist at the University of Dalhousie in Halifax, Nova Scotia, who has no connection to Colossal.

Comments »

If you enjoyed this article, please consider sharing it:

|