20th July 2023 Cryopreservation breakthrough: mammalian kidney transplanted The first successful transplant of a functional cryopreserved mammalian kidney is reported by the University of Minnesota. This occurred after 100 days of storage at below –140°C.

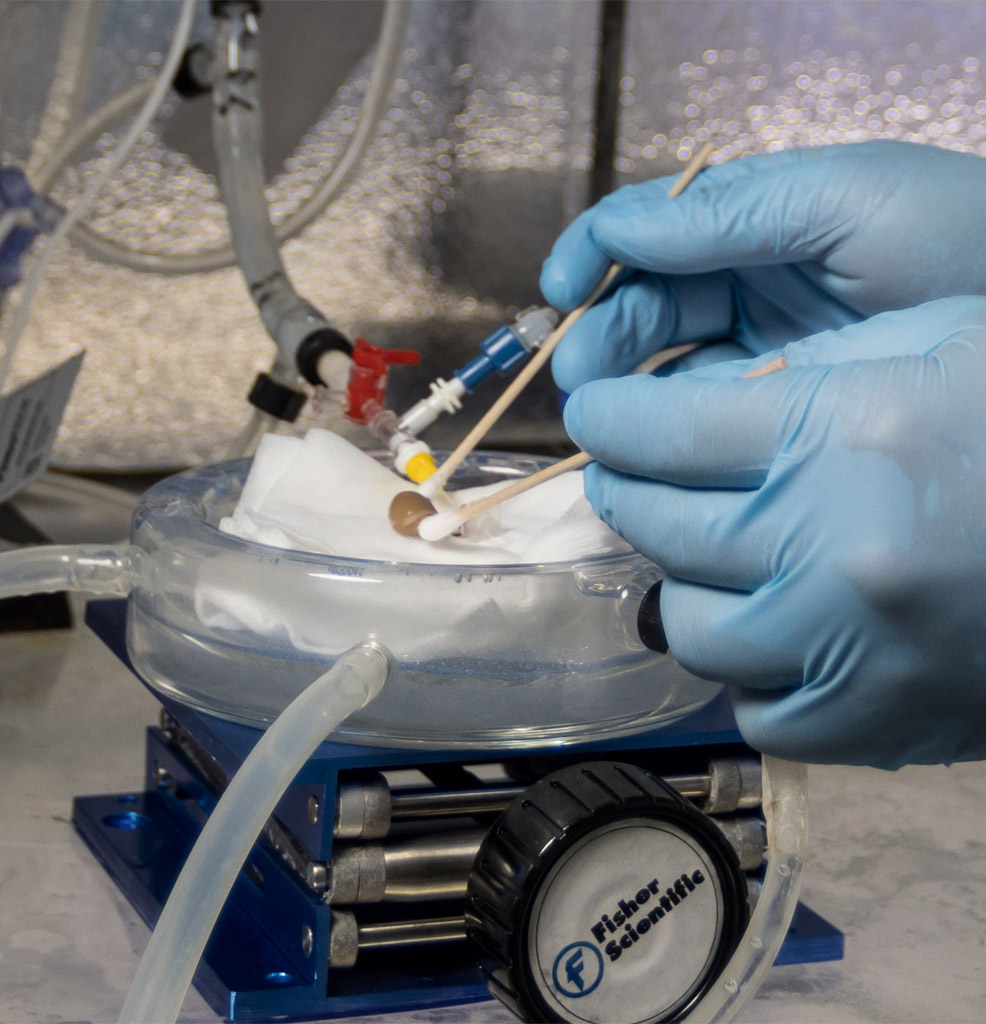

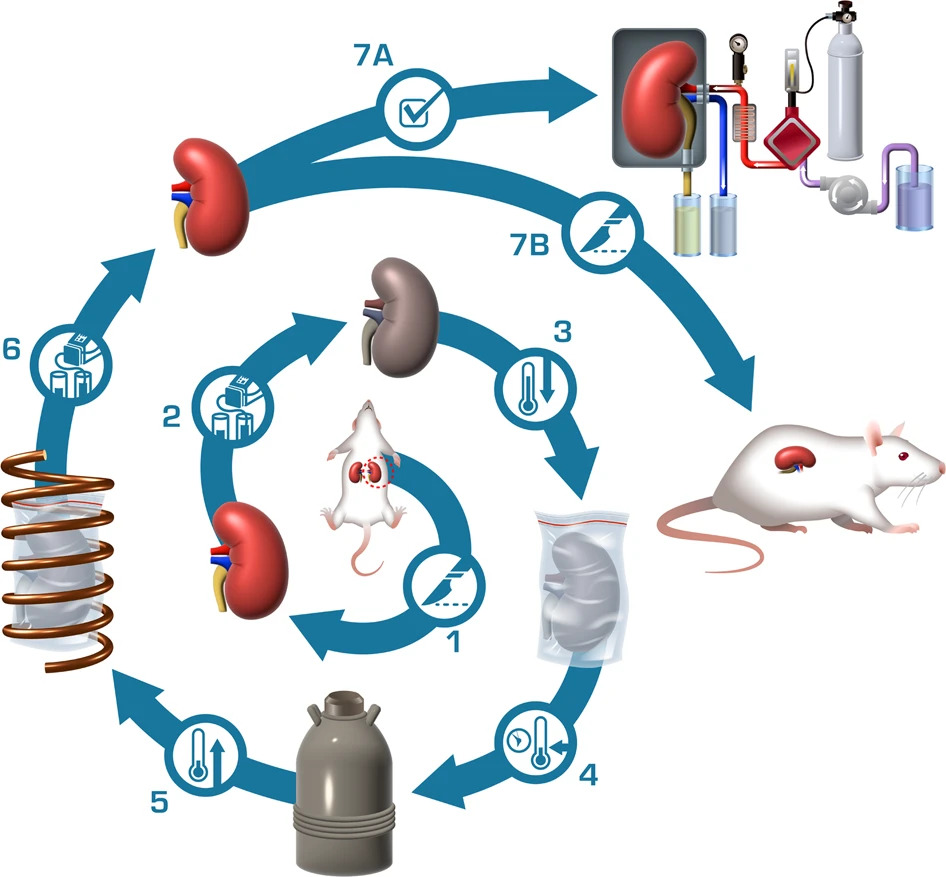

2023 is proving to be a breakthrough year for cryopreservation, with several important developments in the field. This technology has the potential to revolutionise organ transplantation, by substantially extending the preservation period after donation. It could reduce organ waste, enable better matching between donors and recipients, and potentially alleviate the organ shortage crisis, saving thousands of lives each year. In the U.S. alone, about 100,000 adults and children await a replacement organ, with only 41,000 receiving one last year. In the longer term – perhaps within the lifetime of people alive today – cryopreservation could also pave the way for more ambitious applications. It might be used to suspend and revive entire organisms, a concept often seen in science fiction. Long-term preservation of human bodies or brains could provide a form of 'medical time travel' for those with incurable diseases, allowing them to be revived when treatments are available. It could also play a crucial role in space travel, with astronauts placed in a state of suspended animation for long-duration missions. For now, these ideas may appear far-fetched, but the science is progressing bit by bit, as new techniques and innovations continue to push the boundaries of what is possible. Biomedical gerontologist Aubrey de Grey has predicted that the first mouse revival from cryopreservation will occur before 2035. At the recent American Transplant Congress held in San Diego, California, scientists revealed they had stored viable human livers at below-freezing temperatures for 79 hours (more than three days), nearly tripling their previous record of 27 hours. This duration is nine times the clinical standard preservation period using conventional methods. In another breakthrough, researchers from Johns Hopkins University, in collaboration with Sylvatica Biotech, announced the successful transplantation of mammalian limbs after three days of storage at below-freezing temperatures. This could potentially enable more limb, hand, or facial transplants by mitigating issues related to donor-recipient matching. An even more remarkable advancement came to light during the latest annual meeting of the Association of Organ Procurement Organizations. A team described the first successful procedure to store mammalian transplant organs at deep cryogenic temperatures (below –140°C). These organs were preserved for 100 days before being warmed to body temperature and transplanted into rats. The process involved "nanowarming," which employs alternating magnetic fields to heat nanoparticles within the organ vasculature, to achieve both rapid and uniform warming, after which the nanoparticles are removed by perfusion.

Nanowarming process. Credit: Zonghu Han, et al. (2023)

The researchers, from the University of Minnesota, experimented on rat kidneys. Their study proved that these organs could be cryogenically stored, rewarmed, cleared of cryoprotective fluids and nanoparticles, and transplanted into live animals. Five rats underwent the procedure and within 30 days had kidney functions fully restored, without additional interventions. "During the first two to three weeks, the kidneys weren't at full function, but by three weeks, they recovered. By one month, they were fully functioning kidneys that were completely indistinguishable from transplants of a fresh organ," said the study's co-senior author Erik Finger, PhD, a transplant surgeon and professor of surgery at the University of Minnesota Medical School. "This is the first time anyone has published a robust protocol for long-term storage, rewarming, and successful transplantation of a functional preserved organ in an animal," said John Bischof, PhD, Professor of Mechanical and Biomedical Engineering. "All of our research over more than a decade and that of our colleagues in the field has shown that this process should work, then that it could work, but now we've shown that it actually does work." "We have been working on this process for years to make sure everything was in place before we transplanted into a rat," said Michael Etheridge, from the Department of Mechanical Engineering. "It is a very complicated process. I'm very proud of our team." The researchers claim that all aspects of this approach can be scaled to larger organs and will next look to demonstrate the process using pig kidneys. While it will take several years before a cryopreserved organ can be transplanted into humans, the team is confident that it could successfully be done in the future.

Comments »

If you enjoyed this article, please consider sharing it:

|