27th September 2025 Underground carbon storage can only cut warming by 0.7 °C New research finds that safe and practical geologic storage of CO2 emissions is far more limited than once believed, with global reserves capped at 1,460 gigatonnes. Many scenarios could exhaust this by 2100 and virtually all by 2200.

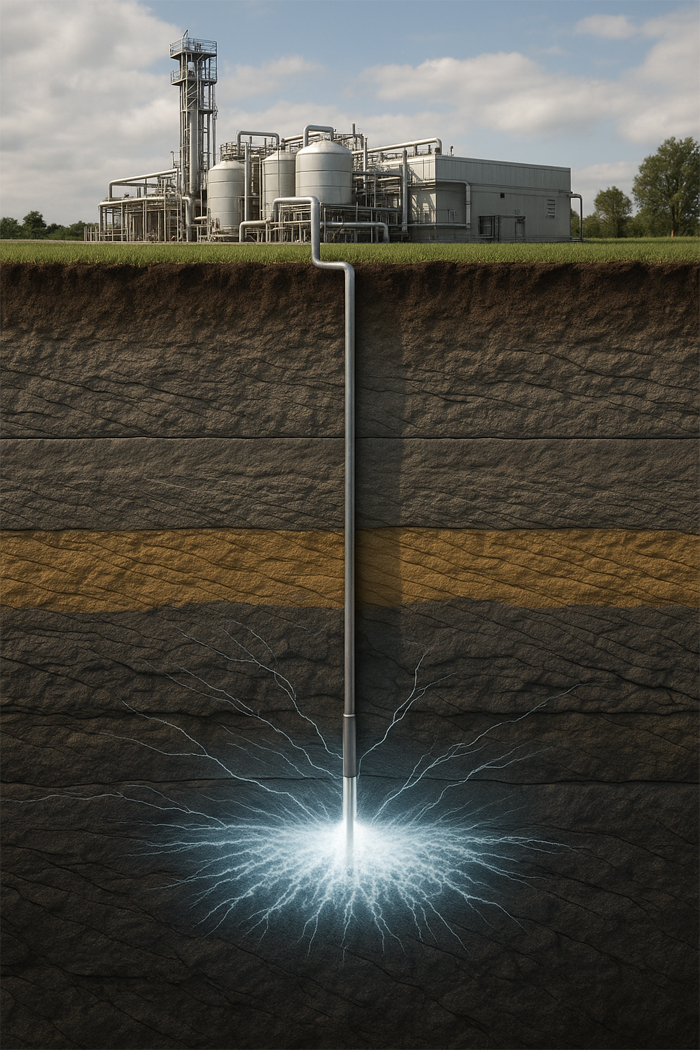

A new study led by the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) and published this month in Nature delivers sobering news for climate policy. For years, many governments and scientists have assumed that vast underground reserves of porous rock could act as an almost limitless vault for storing captured carbon dioxide. This expectation has underpinned a wide range of climate scenarios, particularly those in which the world delays deep cuts to fossil fuels and later tries to compensate with carbon capture and storage. But the new analysis overturns those assumptions. By applying detailed risk factors to global sedimentary basins, the authors conclude that only around 1,460 gigatonnes of CO₂ can be safely and sustainably stored underground. That figure is an order of magnitude smaller than earlier technical estimates of 10,000–40,000 gigatonnes. At this revised scale, even if humanity makes full use of the storage limit, global average temperatures could only be reduced by about 0.7 °C – nearly ten times less than some previous expectations. The researchers arrived at this lower figure by filtering out storage sites that pose unacceptable risks. They only allowed depths of between 1 and 2.5 kilometres – the range at which carbon dioxide can remain in a safe and dense state over the long term – and ruled out areas too close to earthquake zones. They also excluded nature reserves, the Arctic and Antarctic polar circles, and everything within a 25 km (16 mi) buffer around urban areas, where leaks could threaten human health. For offshore sites, they limited storage to waters shallower than 300 metres and within each nation's recognised economic zone, while also applying a six-nautical-mile (7 mi) buffer near international borders to prevent disputes. These safeguards slashed the original theoretical storage potential by almost 90%, leaving a far smaller and more realistic capacity. "There are still many unknowns around geological carbon storage," said lead author Matthew Gidden, a senior researcher in the IIASA Energy, Climate, and Environment Program. "Previous research identified sites that carry serious risks to humans and the environment and make rosy assumptions about how much carbon can be stored there. Our study asks and answers the opposite question: how much of the storage is actually safe and realistic to use?" The authors note that countries such as the USA, Russia, China, Brazil, and Australia retain a high storage potential even after their strict risk filters are applied. By contrast, India, Norway, Canada, and much of the European Union lose a far greater share of their capacity under the same assessment.

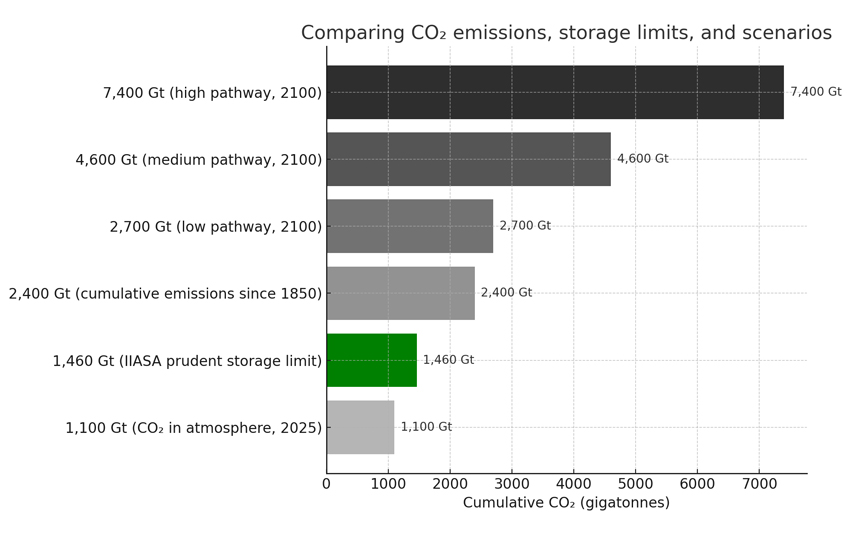

To put the numbers in perspective, the world currently emits about 38 gigatonnes of CO₂ each year from fossil fuels and industry. This means the entire global storage budget equates to less than 40 years of emissions at today's rate. If we compare with the historical record, human activity has released a cumulative 2,400 gigatonnes of CO₂ since the start of the Industrial Revolution. Of that total, about 1,300 gigatonnes has been absorbed by oceans and land ecosystems, while about 1,100 gigatonnes remains in the atmosphere today. In other words, the CO₂ still in the air already amounts to 75% of the underground storage limit. Looking ahead, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projects that future emissions could vary widely, depending on how the world responds. On a low-emissions pathway (SSP1-1.9), annual emissions fall to net zero around mid-century, with the cumulative total since the Industrial Revolution reaching 2,700 gigatonnes by 2100. A medium pathway (SSP2-4.5), consistent with current national policies, pushes the total closer to 4,600 gigatonnes by 2100. In the high-emissions case (SSP5-8.5), humanity would generate 7,400 gigatonnes by the end of the century. The IIASA's new analysis shows why this matters for policy. The IPCC assesses thousands of modelled pathways, not just a single low, medium, or high track. After applying strict geological, environmental, and societal safeguards, the authors set a "prudent" storage limit of 1,460 gigatonnes of CO₂ and estimated that even full use of this capacity would cut warming by only 0.7 °C. When you compare this limit with the wider ensemble of IPCC pathways, a significant share will breach it before 2100 if society leans heavily on underground injection, and virtually all will do so by 2200. This turns geologic storage from a presumed backstop into a scarce resource – one that should be managed carefully and reserved for the hardest-to-abate emissions in sectors like cement, steel, and aviation.

This study also raises questions of fairness. Countries such as the United States, Russia, and Saudi Arabia have large reserves of suitable geology, while others like India or those in the European Union face much tighter constraints. If storage becomes a traded commodity in future, vast flows of captured carbon may need to be shipped or piped across borders, raising issues of cost, safety, and equity. Until now, climate modelling often assumed that geologic storage could be scaled up almost without limit. The IIASA team shows that this is no longer the case. Current trends put humanity on course for 3 °C of global warming this century, so even if the maximum available storage capacity is used, the resulting drop of less than one degree would still leave temperatures above the 2 °C safety threshold. We therefore cannot rely on storage as a get-out-of-jail card. The only viable path forward is to slash emissions at the source, as quickly as possible, while using underground injection sparingly and strategically. This is obviously bad news for climate change in the longer term. The safety margin that policymakers believed they had is far smaller than expected, and the clock is ticking faster. Decarbonisation efforts, already urgent, are now more important than ever.

Comments »

If you enjoyed this article, please consider sharing it:

|

||||||