6th September 2013 Scientists confirm existence of largest single volcano on Earth A team of scientists has found the largest single volcano yet documented on Earth. Covering an area roughly equivalent to the British Isles or the state of New Mexico, this underwater volcano – the Tamu Massif – is nearly as big as the giant volcanoes of Mars, placing it among the largest in the Solar System.

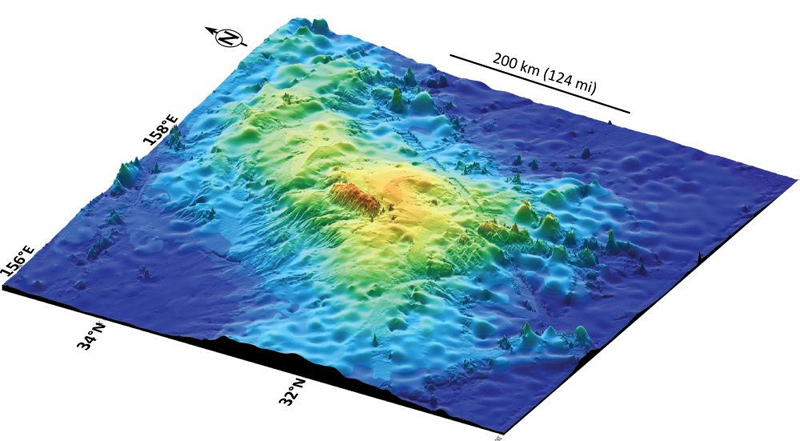

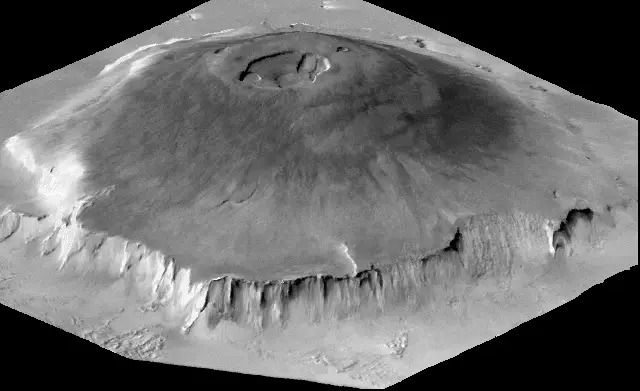

Located about 1,000 miles east of Japan, Tamu Massif is the largest feature of Shatsky Rise, an underwater mountain range formed 130 to 145 million years ago by the eruption of several underwater volcanoes. Until now, it was unclear whether Tamu Massif was a single volcano, or a composite of many eruption points. By integrating several sources of evidence, including core samples and data from the JOIDES Resolution research ship, the authors have confirmed that the mass of basalt that constitutes Tamu Massif did indeed erupt from a single source near the centre. “Tamu Massif is the biggest single shield volcano ever discovered on Earth,” said William Sager, a professor in the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at the University of Houston (UH), who first began studying the volcano about 20 years ago. “There may be larger volcanoes – because there are bigger igneous features out there such as the Ontong Java Plateau – but we don't know if these features are one volcano, or complexes of volcanoes.” Tamu Massif stands out among underwater volcanoes not just for its size, but also its shape. It is low and broad, meaning that the erupted lava flows must have travelled long distances compared to most other volcanoes on Earth. The seafloor is dotted with thousands of underwater volcanoes, or seamounts, most of which are small and steep compared to the low, broad expanse of Tamu Massif. “It’s not high, but very wide, so the flank slopes are very gradual,” Sager said. “In fact, if you were standing on its flank, you would have trouble telling which way is downhill. We know that it is a single immense volcano constructed from massive lava flows that emanated from the centre of the volcano to form a broad, shield-like shape. Before now, we didn't know this because oceanic plateaus are huge features hidden beneath the sea. They have found a good place to hide.” Tamu Massif covers an area of about 120,000 square miles. By comparison, Hawaii’s Mauna Loa – the largest active volcano on Earth – is approximately 2,000 square miles, or roughly 2 percent the size of Tamu Massif. To find a worthy comparison, one must look skyward to the planet Mars, home to Olympus Mons. That volcano, pictured below, is only about 25 percent larger by volume than Tamu Massif.

The study relied on two distinct, yet complementary, sources of evidence – core samples from an ocean drilling program collected in 2009, and seismic reflection data gathered on two separate expeditions in 2010 and 2012. The core samples, drilled from several locations on Tamu Massif, showed that thick lava flows (up to 75 ft thick), characterise this volcano. Seismic data revealed the structure of the volcano, confirming that the lava flows emanated from its summit and flowed hundreds of miles downhill into the adjacent basins. According to Sager, Tamu Massif formed 145 million years ago – placing it on the border between the Jurassic and the Cretaceous periods – and became inactive within a few million years of erupting. Its top lies about 6,500 feet below the ocean surface, while much of its base is believed to be in waters that are almost four miles deep. “Its shape is different from any other sub-marine volcano found on Earth, and it’s very possible it can give us some clues about how massive volcanoes can form,” added Sager. “An immense amount of magma came from the centre, and this magma had to have come from the Earth’s mantle. So this is important information for geologists trying to understand how the Earth’s interior works.” Sager and his team's findings appear in the latest issue of Nature Geoscience.

Comments »

|