12th March 2016 New plastic-eating bacteria discovered The first species of bacteria able to degrade polyethylene terephthalate (PET) has been described by Japanese researchers.

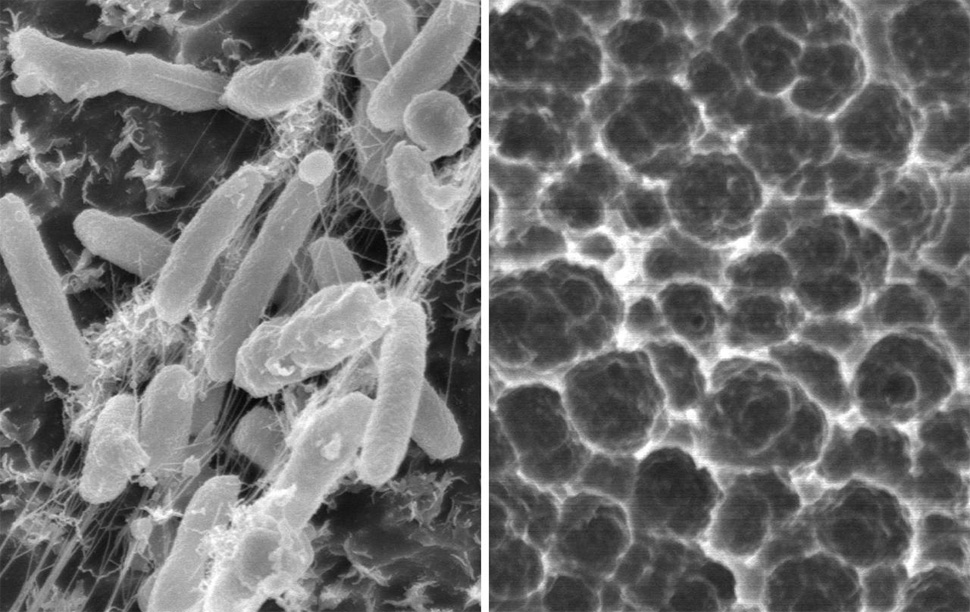

The first species of bacteria able to degrade polyethylene terephthalate (PET) has been described by Japanese researchers. PET is a type of polymer used in plastic that is highly resistant to biodegradation. About 56 million tons of PET was produced worldwide in 2013 alone, and its accumulation in ecosystems around the globe is increasingly problematic. To date, very few species of fungi – but no bacteria – have been found to break down PET. In their new study published yesterday, Yoshida et al. collected 250 samples of PET debris and screened for bacterial candidates that depend on PET film as a primary source of carbon for growth. A novel bacterium was identified, which could almost completely degrade a thin film of PET after six weeks of exposure at 30°C (86°F). They have named the organism Ideonella sakaiensis. Further investigation identified an enzyme, ISF6_4831, which works with water to break down PET into an intermediate substance, which is then further broken down by a second enzyme, ISF6_0224. These two enzymes alone can break down PET into simpler building blocks. Remarkably, they seem to be highly unique in their function compared to the closest related known enzymes of other bacteria, raising questions of how this plastic-eating bacteria species originated. Rapid evolution, in as little as 70 years, may have occurred in response to the build-up of plastic in the environment, according to Enzo Palombo, professor of microbiology at Swinburne University in Australia: "If you put a bacteria in a situation where they've only got one food source to consume, over time they will adapt to do that," he said. "This is the first rigorous study – it appears to be very carefully done – that I have seen that shows plastic being hydrolysed [broken down] by bacteria," said Dr Tracy Mincer, a researcher at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, USA. "I think we are seeing how nature can surprise us and in the end the resiliency of nature itself." However, the bacteria took longer to degrade highly crystallised PET, which is used in plastic bottles. That means the enzymes and processes would need refinement before they could be used in recycling, ocean clean-up, or other environmental regeneration projects. "It's difficult to break down highly crystallised PET," said Prof Kenji Miyamoto from Keio University, one of the paper's co-authors. "Our research results are just the initiation for the application. We have to work on so many issues needed for various applications. It takes a long time." Future studies would also need to determine if the bacteria can survive in salty seawater and fluctuating ocean temperatures. There might be additional species out there, which have already adapted for these conditions, and just need to be found, says Palombo: "I would not be surprised if samples of ocean plastics contained microbes that are happily growing on this material and could be isolated in the same manner," he said. The study was published yesterday in Science. ---

Comments »

|