4th April 2017 Graphene sieve turns seawater into drinking water Researchers at the University of Manchester have demonstrated a graphene-based sieve able to filter seawater. This could lead to affordable desalination technologies.

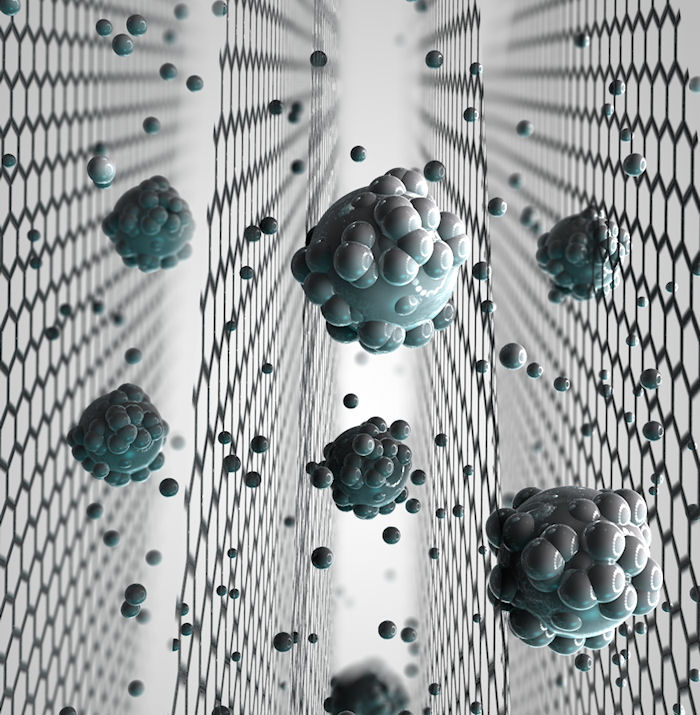

In recent years, graphene-oxide membranes have attracted major attention as promising candidates for new filtration technologies. Now, the much sought-after breakthrough of making membranes capable of sieving common salts has been achieved. New research demonstrates the real-world potential of providing clean drinking water for millions of people who currently struggle to obtain adequate water resources. The findings, by scientists from the University of Manchester, were published yesterday in the journal Nature Nanotechnology. Graphene-oxide membranes developed at the National Graphene Institute have already demonstrated the potential of filtering out small nanoparticles, organic molecules, and even large salts. Until now, however, they couldn't filter common salts, which require even smaller sieves. Previous research at the University of Manchester found that if immersed in water, graphene-oxide membranes become slightly swollen and smaller salts flow through the membrane along with water, but larger ions or molecules are blocked. The team has now further developed these graphene membranes and found a way to prevent the swelling of the membrane when exposed to water. Pore size in the membrane can be precisely controlled, to filter common salts out of salty water and make it safe to drink.

As the effects of climate change continue to impact on water supplies, wealthy countries are also investing in desalination technologies. Following the recent disasters in California, major cities are looking increasingly to alternative water solutions. When common salts are dissolved in water, they form a 'shell' of water molecules around the salt molecules. This allows the tiny capillaries of the graphene-oxide membranes to block salt from flowing along with the water. Water molecules are able to pass through the membrane barrier and flow anomalously fast, which is ideal for application of these membranes for desalination. "To make it permeable, you need to drill small holes in the membrane. But if the hole size is larger than one nanometre, the salts go through that hole," said Rahul Nair, Professor of Materials Physics. "You have to make a membrane with a very uniform, less-than-one-nanometre hole size to make it useful for desalination. It is a really challenging job. When the capillary size is around one nanometre, which is very close to the size of the water molecule, those molecules form a nice interconnected arrangement, like a train." "Realisation of scalable membranes with uniform pore size down to the atomic scale is a significant step forward and will open new possibilities for improving the efficiency of desalination technology," he continued. "This is the first clear-cut experiment in this regime. We also demonstrate that there are realistic possibilities to scale up the described approach and mass produce graphene-based membranes with required sieve sizes." "The developed membranes are not only useful for desalination, but the atomic scale tunability of the pore size also opens new opportunity to fabricate membranes with on-demand filtration, capable of filtering out ions according to their sizes." said Jijo Abraham, co-author on the research paper. By 2025, the UN expects that 14% of the world's population will encounter water scarcity. This new technology has the potential to revolutionise water filtration across the world, particularly in nations which cannot afford large-scale desalination technology. It is hoped that graphene membrane systems can be utilised on smaller scales – making them accessible to regions that do not have the financial infrastructure to fund large plants.

---

Comments »

|