|

|

|

|

|

|

2047

South Korea's "mega chip cluster" is completed

During the 2010s and early 2020s, a series of disruptive events led to mounting concerns over the availability of semiconductors. Chip supply chains had been impacted by the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, record-breaking floods in Thailand, the US-China Trade War, the COVID-19 pandemic, and geopolitical tensions between China and Taiwan.

To improve economic stability and boost its own production capabilities, South Korea announced a long-term plan to build 16 new fabrication facilities over a period of 23 years. This new "mega chip cluster" – the largest of its kind in the world – would involve companies like Samsung Electronics and SK hynix investing a final total of 622 trillion won ($471 billion), equivalent to more than a quarter of the country's annual GDP.

Public funding comprised part of the plan, with South Korea's government providing additional support for relevant infrastructure. With its birth rate among the lowest in the world, and a population predicted to fall by nearly 10% before 2050, policies would also be introduced to attract more experts in the field – such as more flexible visa arrangements for foreigners, alongside the cultivation of local talent by authorities, and tax breaks for local firms.

Samsung Electronics agreed to build six new fabs at a national industrial complex in Yongin, part of the Seoul Capital Area, plus three more fabs in Pyeongtaek, further south, and three research fabs at an R&D centre in Giheung District, further north. Memory chip maker SK hynix planned to construct four fabs at another site in Yongin. A predicted 70,000 jobs would be created during the construction of these 16 fabs, as well as 40,000 at companies supplying parts and materials, with ripple effects beyond the cluster generating 3.5 million employment opportunities nationwide.

By 2030, South Korea had more than tripled its market share of global logic chip production, from 3% to almost 10%. The partially completed mega-cluster now produced 7.7 million wafers monthly and had begun challenging dominant companies in the sector like TSMC and Qualcomm. In addition, South Korea enhanced its self-sufficiency in the supply chain of key materials, which increased from 30% to 50%.

By 2047, with further scaling up and completion of the final production facility,** these figures have improved to an even greater extent, as South Korea strengthens its position as the world's leading chip hub. After moving into the sub-nanometre regime, many companies experimented with next-generation materials such as graphene, which are now mature technologies and firmly established throughout their industry ecosystems. The mega-cluster's vast capacity and technical expertise are playing a major role in the progress of AI and robotics of this time.

Part of the future semiconductor mega-cluster at an industrial complex in Yongin, Gyeonggi. Credit: SK hynix

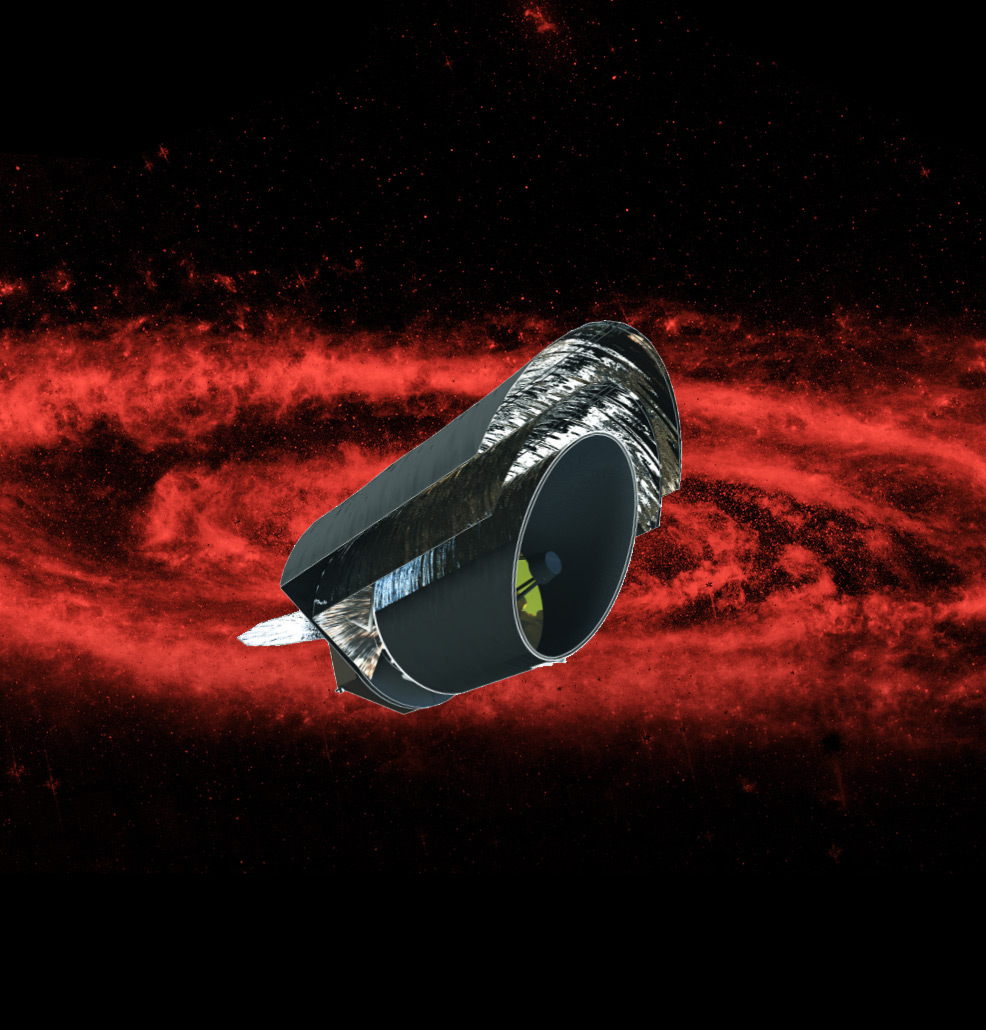

Launch of the Far-Infrared (FIR) Great Observatory

The Far-Infrared (FIR) Great Observatory is the second in a trio of next-generation space telescopes planned by NASA. Launched in 2047, it follows the earlier Habitable Worlds Observatory (HWO) that began operations in 2041.

As its name suggests, the FIR observatory is designed to study astronomical phenomena at far-infrared wavelengths – which are outside the ultraviolet, visible, and near-infrared capabilities of the HWO. It functions as the long-awaited successor to the Spitzer Space Telescope, which had a mission duration of 17 years from 2003 until 2020. Its final design is based partly on an earlier concept known as the Origins Space Telescope.**

While the HWO is focused on the direct imaging of Earth-like planets, the FIR observatory is targeted primarily at galaxies, black holes, molecular clouds and proto-planetary disks. One of its major science objectives is to investigate supermassive black holes – which lurk at the centre of most galaxies – and how they influence star formation. It can use far-infrared spectroscopy to penetrate the dust and gas surrounding these objects, revealing specific spectral lines related to star formation and feedback from black hole winds.

It also traces the journey of water from molecular clouds to proto-planetary disks, providing major insights into the formation of new planetary systems and how life-bearing exoplanets form. This improves the understanding of Earth and its early history too.

Additionally, the FIR generates a near-complete census of the outer Solar System, using its far-infrared capabilities to reveal some of the last remaining undiscovered minor planets beyond Pluto.

Astronomers using the FIR can collaborate with teams using the HWO – and researchers at major new ground-based facilities too, such as the Thirty Metre and Giant Magellan Telescope – to combine and refine their measurements. In studies of exoplanets, for example, the FIR can help to confirm temperatures, atmospheric compositions, and chemical ingredients for life.

The instruments on the FIR observatory are at the cutting edge of astrophysics, with up to 1,000 times the sensitivity and resolution of any previous telescope operating in far-infrared wavelengths. Following the HWO and FIR, a third and final mission in the New Great Observatory series is launched with X-ray capability, beginning science operations a few years later in 2051.* This generation of space telescopes remains in service until the 2070s.*

Fully autonomous, intelligent military aircraft

Most of today's jet fighters are now entirely computer controlled. These unmanned planes have fully autonomous capability from the moment they take off, to the moment they land. A combination of strong AI, swarming behaviour and hypersonic technology is employed to create near-instantaneous effects throughout the battlespace.*

The growth of network-centric warfare and the increasing complexity of enemy types, movements and environmental factors has led to major advances in target recognition technology and collision avoidance systems. This allows whole squadrons of pilotless planes to synchronise, attack from multiple vectors and regroup in seconds. Further autonomy is provided by auto air refueling, self-repair and other systems.

With the emergence of AI, personnel costs have shifted from operations, maintenance and training, to design and development. Machines can perform repairs in-flight (including the use of "self-healing" nanotechnology composites) while routine ground maintenance requires little or no human labour, being done mostly by robots. New tactics and information can simply be programmed into the aircraft, or they can "learn" from others in the swarm.

With their hypersonic engines, inhuman reaction times, and improved weaponry, these craft would run rings around human pilots of earlier decades. Following the retirement of the F-35 Lightning II, manned fighter planes are now largely obsolete.

Credit: DARPA

Unmanned probe to 2060 Chiron

2060 Chiron is a minor planet found in the outer Solar System.* Discovered in 1977, it became the first in a new class of objects known as centaurs – small bodies orbiting between Saturn and Uranus – and named after the race of half-man/half-horses from Greek mythology, in recognition of their dual comet/asteroid nature.

2060 Chiron has a radius of around 145 miles (233 km) and a parabolic orbit going from just inside the orbit of Saturn (8.5 AU) to just outside the orbit of Uranus (19 AU). With an orbital period of 51 years, it reaches perihelion in 2047.* As part of the recent exploration of the Kuiper Belt, an unmanned robotic probe has been sent to intercept it, arriving this year.

The mission returns vital data about Chiron's size, shape, polar obliquity, atmosphere, surface morphology, composition, internal structure, surface activity (including the nature of Chiron's outbursts), and its origin. NASA had been planning for such a mission as far back as 1994.*

« 2046 |

⇡ Back to top ⇡ |

2048 » |

If you enjoy our content, please consider sharing it:

References

1 Korea unveils plan to build $471 bil. mega chip cluster in Gyeonggi Province, The Korea Times:

https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/tech/2024/01/133_366948.html

Accessed 17th January 2024.

2 What is South Korea's 'semiconductor mega cluster' and why is it important?, Arirang News / YouTube:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=APx2am74Fac

Accessed 17th January 2024.

3 The Far Infrared Observatory, The New Great Observatories:

https://www.greatobservatories.org/fir

Accessed 1st February 2023.

4 Origins Space Telescope, Wikipedia:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Origins_Space_Telescope

Accessed 1st February 2023.

5 NASA prepares next steps in development of future large space telescope, SpaceNews:

https://spacenews.com/nasa-prepares-next-steps-in-development-of-future-large-space-telescope/

Accessed 1st February 2023.

6 "The timescales involved are phenomenal. If Hubble and Chandra are anything to go by, the next-generation telescopes launched in the 2040s could still be operational in the 2070s or beyond."

See 'Great observatories' – the next generation of NASA's space telescopes, and their impact on the next century of observational astronomy, Physics World:

https://physicsworld.com/a/great-observatories-the-next-generation-of-nasas-space-telescopes

Accessed 1st February 2023.

7 United States Air Force Unmanned Aircraft Systems Flight

Plan 2009-2047, GlobalSecurity.org

http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/policy/usaf/usaf-uas-flight-plan_2009-2047.htm

Accessed 14th August 2010.

8 2060 Chiron, Wikipedia:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2060_Chiron

Accessed 8th July 2012.

9 The Chiron Perihelion Campaign, NASA:

http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/chiron.html

Accessed 8th July 2012.

10 A Low-Cost Mission to 2060 Chiron Based on the Pluto Fast Flyby, NASA:

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20060039487

Accessed 1st February 2023.

![[+]](https://www.futuretimeline.net/images/buttons/expand-symbol.gif)