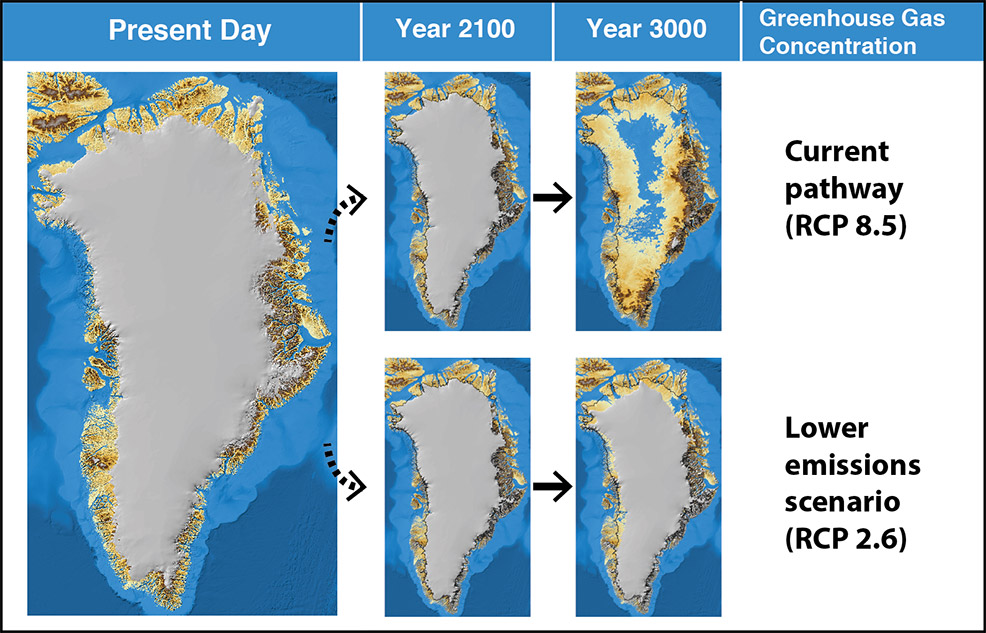

24th June 2019 Greenland may be ice-free by the year 3000 New research concludes that an iceless Greenland may be in the future. If the rising level of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) remains on its current trajectory, Greenland may be ice-free by the year 3000. Even by the end of the 21st century, the island could lose almost 5% of its ice – contributing up to 33 cm (13") of global sea level rise.

"How Greenland will look in the future – in a couple of hundred years, or in 1,000 years – whether there will be Greenland, or at least a Greenland similar to today, it's up to us," said Andy Aschwanden, a research associate professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute. Aschwanden is lead author on a new study published in the June issue of Science Advances. This research uses new data on the landscape under the ice today to improve models of the future. The findings show a wide range of scenarios for ice loss and sea level rise based on different projections for greenhouse gas concentrations and atmospheric conditions. Currently, the planet is moving toward the high estimates. Greenland's ice sheet is huge, spanning over 660,000 square miles. It is almost the size of Alaska and 80% as big as the U.S. east of the Mississippi River. Today, the ice sheet covers 81% of Greenland and contains 8% of Earth's fresh water. If greenhouse gas concentrations remain on the current path, melting ice from Greenland alone could contribute as much as 7.3 m (24 ft) to global sea level rise by the year 3000. This would put vast swathes of coastline and hundreds of major cities all over the world under water. However, if greenhouse gas emissions are cut significantly, that picture changes. Instead, by 3000 Greenland may lose between 8% and 25% of its ice and contribute 2 m (6.5 ft) of sea level rise. Projections for both the end of the century and 2200 tell a similar story. There is a wide range of possibilities – including saving the ice sheet – but it all depends on greenhouse gas emissions.

The researchers ran 500 simulations for each of the three climate scenarios using the Parallel Ice Sheet Model, developed at the Geophysical Institute, to create a picture of how Greenland's ice would respond in the future. This model included parameters on both ocean and atmospheric conditions, as well as ice geometry, flow and thickness. Simulating ice sheet behaviour is difficult, because ice loss is led by the retreat of outlet glaciers. These glaciers, at the margins of ice sheets, drain the ice from the interior like rivers, often in troughs hidden under the ice itself. This study is the first model to include these outlet glaciers. It found that their discharge could contribute as much as 45% of the total mass of ice lost in Greenland by 2200. Outlet glaciers are in contact with water, and water makes ice melt faster than contact with air, like thawing a chicken in the sink. The more ice touches water, the faster it melts, creating a feedback loop. The team used data from a NASA airborne science campaign called Operation IceBridge, which uses aircraft equipped with a full suite of scientific instruments, including three types of radar that can measure the ice surface, the individual layers within the ice and penetrate to the bedrock to collect data about the land beneath the ice. On average, Greenland's ice sheet is 1.6 miles thick, but there is a lot of variation depending on where you measure. "Ice is in very remote locations," explains co-author Mark Fahnestock. "You can go there and make localised measurements. But the view from space, and the view from airborne campaigns, like IceBridge, has just fundamentally transformed our ability to make a model to mimic those changes." As for what we will actually see in the future, "it depends on what we are going to do next."

Comments »

If you enjoyed this article, please consider sharing it:

|