30th July 2020 AI can spot prostate cancer with almost 100% accuracy A new AI algorithm developed by the University of Pittsburgh has achieved the highest accuracy to date in identifying prostate cancer, with 98% sensitivity and 97% specificity.

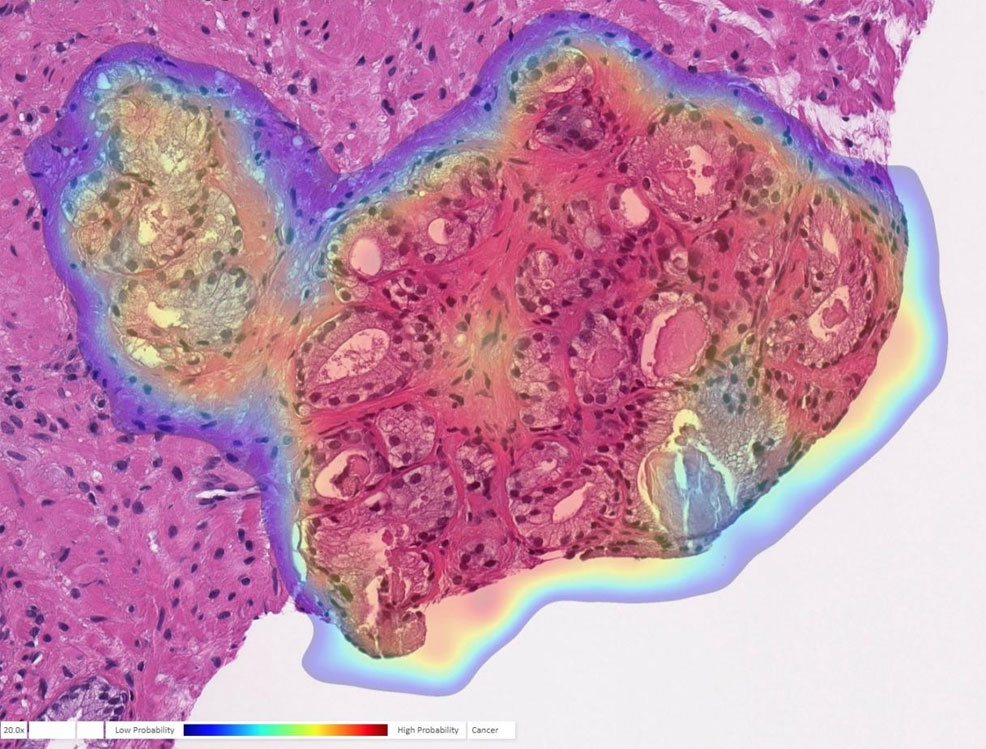

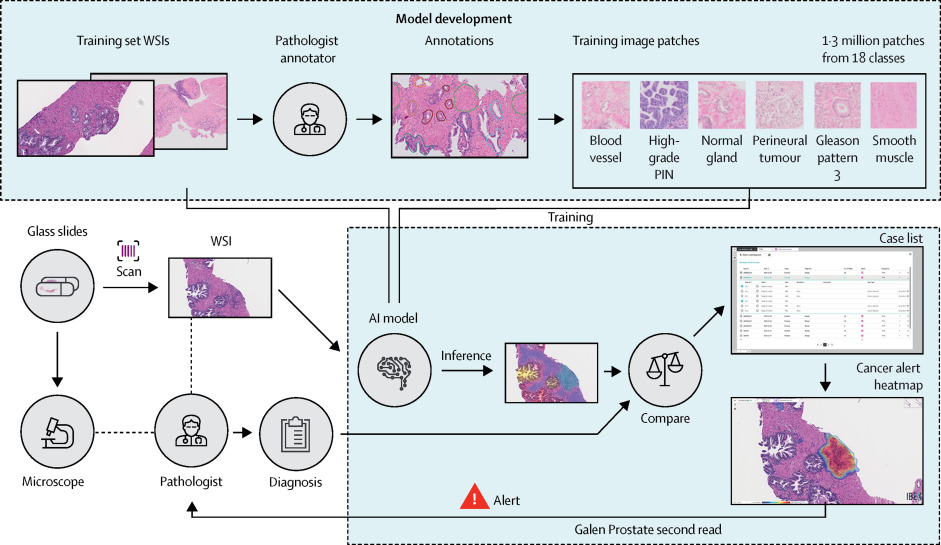

A study published this week in The Lancet Digital Health by University of Pittsburgh researchers demonstrates the highest accuracy to date in recognising and characterising prostate cancer using an artificial intelligence (AI) program. "Humans are good at recognising anomalies, but they have their own biases or past experience," said Rajiv Dhir, Professor of Biomedical Informatics at Pitt. "Machines are detached from the whole story. There's definitely an element of standardising care." To train the AI to recognise prostate cancer, Dhir and his colleagues provided images from more than a million parts of stained tissue slides taken from patient biopsies. Expert pathologists labelled each image to teach the AI how to discriminate between healthy and abnormal tissue. The algorithm was then tested on a separate set of 1,600 slides from 100 consecutive patients, seen at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) for suspected prostate cancer. During testing, the AI demonstrated 98% sensitivity and 97% specificity at detecting prostate cancer – significantly higher than previously reported for algorithms working from tissue slides.

Also, this is the first algorithm to extend beyond cancer detection, reporting high performance for tumour grading, sizing and invasion of the surrounding nerves. These are all clinically important features, required as part of the pathology report. The AI flagged six slides that were missed by the expert pathologists. However, Professor Dhir explains that this does not necessarily mean that the machine is superior to humans. For example, while evaluating these cases, a pathologist could have simply seen enough evidence of malignancy elsewhere in that patient's samples to recommend treatment. For less experienced pathologists, though, the algorithm could act as a failsafe to catch cases that might otherwise be missed. "Algorithms like this are especially useful in lesions that are atypical," Dhir said. "A non-specialised person may not be able to make the correct assessment. That's a major advantage of this kind of system." While these results are promising, Dhir cautions that new algorithms will have to be trained to detect different types of cancer. The pathology markers are not universal across all tissue types. But he believes this technology could be adapted to work with breast cancer, for example.

--- Follow us: Twitter | Facebook | Instagram | YouTube

Comments »

If you enjoyed this article, please consider sharing it:

|