Space art by Mark A. Garlick

Mark specialises in dramatic imagery of space, geology, dinosaurs, aliens, post-apocalyptic scenes and the far future. NASA has sometimes used his work to illustrate planets, stars and other astronomical phenomena. His artwork appears in the background for one of our predictions: 900,000 AD – The next Yellowstone super-eruption.

Below are some of his more future-oriented pieces, along with a showreel of video animations he produced. If you like these, be sure to check out the rest of his work at markgarlick.com and space-art.co.uk. He can also be followed on Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.

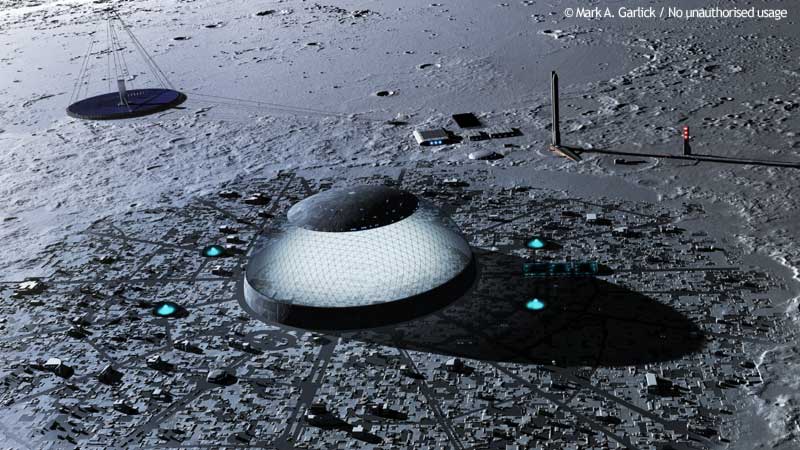

Over the next few decades, humans may begin to settle on the Moon. In the more distant future, perhaps entire cities may form. Mark provides a tantalising glimpse of what such a colony might look like.

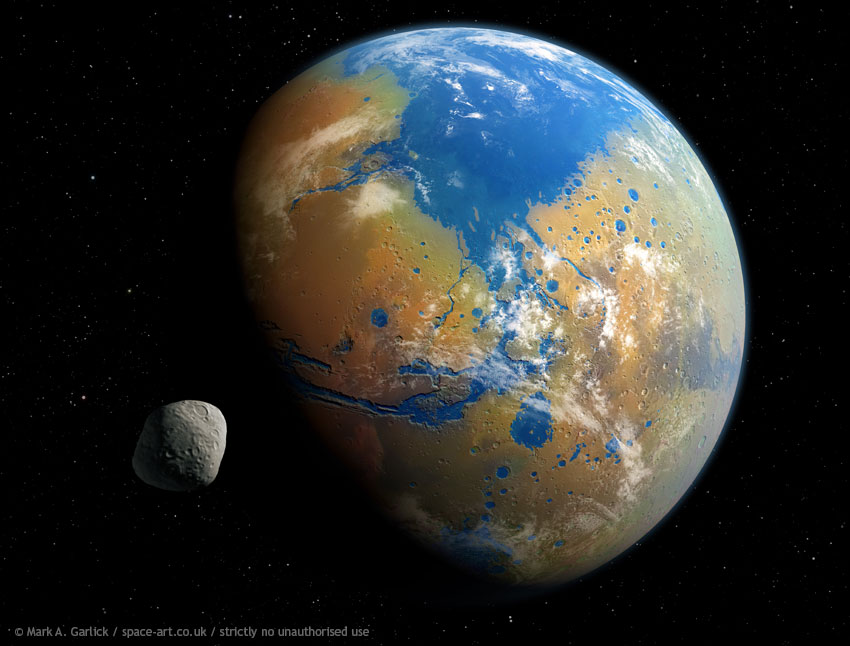

Mars contains a huge quantity of water – both hidden underground, and frozen on the surface – the remnants of its ancient past. There is enough to cover the whole planet to a depth of 35 metres (115 ft). Humanity may attempt to terraform the planet in the far future, with potential to create a utopia that resembles an unspoilt Earth. In Mark's illustration, the results of that centuries-long process can be seen, with its northern lowlands transformed into a new ocean that flows down to Valles Marineris. The outermost moon, Deimos, is in the foreground.

Artwork of the M87 black hole, seen from a nearby planet. This was famously imaged in 2019 by a team of astronomers using the Event Horizon Telescope and became the first image of a black hole's accretion disc to ever be directly captured. While exceedingly hot, the surrounding accretion disc is nearly invisible in the optical part of the spectrum because most of its luminosity is in the X-ray part of the spectrum. The jets of charged particles, however, moving at a sizeable fraction of the speed of light, are clearly visible. Perhaps in the future, our descendants may get to witness incredible sights like this.

Then again, our dream of reaching the stars may fail to materialise. This is one of Mark's post-apocalyptic visions.

A brief glimpse of Mark's astronomy animations, most of which can be found in their entirety elsewhere on his channel.

We spoke to Mark about his work.

Could you tell us about your background, and how you first got into art, and video animation?

I come from humble beginnings. I never had a clear vision of what I wanted to be when I was a youngster in London – I just knew I loved space and dinosaurs. Being from a working-class background with nobody in my family having any higher education, university wasn't even on my radar. It wasn't until a friend asked me what I was going to do after school that I seriously started thinking about a degree. I considered art, which I'd always had a natural talent for, but decided that wasn't for me. I wanted to know more about the universe around us. Black holes, relativity, quantum mechanics – these are the subjects that excited me.

So I decided to do a degree (BSc) in astronomy at University College London (UCL). I was accepted to the course, and spent three years filling my brain with space, physics and mathematics. Then I hit another wall. I had a degree in astronomy – so what next? I didn't feel ready for work, so I opted to study for a PhD in astrophysics at the Mullard Space Science Laboratory, a department of UCL but based outside of London. I spent four years researching interacting binary stars – where a tiny dead star called a white dwarf orbits a red dwarf very closely, stretches the latter into an egg shape and steals material from it to wrap itself in a vast pancake of gas called an accretion disc. Authoring my thesis and the scientific papers that went into it gave me an interest in writing.

I graduated with my PhD aged 25 in 1993, then moved to Brighton on the south coast of England to take up a three-year postdoctoral research fellowship in theoretical astrophysics at the University of Sussex. It was at this point I began to get fed up with astronomy as a career. I still loved the subject – and in my spare time I was painting space art in acrylic and oil pastels – but I felt I had taken astronomy as far as I could. A friend of mine at that time began working as an editor on a new space magazine called Modern Astronomer, and so I began writing articles for him and providing illustrations from the portfolio of artwork I had built up over the years in my spare time. When my postdoctoral work ended in 1996, I decided to become a full-time freelance writer and illustrator, and was fortunate enough that I had by then acquired enough contacts to help me make that happen.

In 1998 I started doing artwork digitally for the first time – with a mouse! (One of my first ever digital artworks, done before I had discovered graphics pads, won a digital space art contest in 1998!) In 2000 I wrote my first book called The Story of the Solar System, which was published by Cambridge University Press. Over these last twenty years, I have managed to carve out a successful career as an author and digital illustrator. I have written six books to date, most of which I also illustrated, and of course illustrated many more books by other writers.

The animation work came later, around 2010. I had used 3DS Max for years by then, but only for stills. I decided I needed to bring my scenes to life, and I taught myself how to create animations. I look back on my career and consider it ironic I decided against doing art at university, since art is now my main career. I am entirely self-taught in art, writing and computer animation, and very proud of what I have achieved – so far. Most of my clients are either magazines, book publishers, or scientists who commission me for press-release images.

Do you have a particular favourite subject, object or theme you most enjoy illustrating?

Yes, anything with drama in it. So that usually means scenes depicting things crashing into other things – asteroid impacts, for example – or things exploding. I recently animated a moon breaking up as it ventured too close to Saturn and got torn apart by tidal forces. That was fun! I also enjoy depicting exoplanets.

What software do you use?

As mentioned above, I am a long-time user of 3DS Max. But my main software, like most illustrators, is Photoshop. I am also now very familiar with Blender, and it is my go-to program for space animation. I use After Effects for video editing. I've also used software such as Bryce, Terragen and Vue, but not anymore.

How long does a typical piece of your artwork take to complete?

It can vary from a couple of hours to a few days for a still. Animations take much longer – from a day for a simple scene to a couple of months for much more complex ones.

What advice would you give to other aspiring artists?

'Never give up, never surrender!' Seriously, though, it can be tough. And although it's a cliché, it is also sadly quite often true that 'it's not what you know, but who'. But don't be discouraged.

First off, join an artist or illustrator association. I am a Fellow of the International Association of Astronomical Artists (IAAA.org), and they are great if you want to get into space art. Then, you need to get to know your potential clients, learn which magazines, publishers, whatnot, will actually want to publish your work. No sense sending a beautifully rendered painting of a spiral galaxy to a magazine called, I don't know, Horse and Countryside. Okay, extreme example, but you get the picture. Once you know what sort of art you want to do and who will want to print it, get in touch with them. You can find out how to contact them in publications such as Writers' and Artists' Yearbook (in the UK, but no doubt other countries have similar tomes). Send your target clients some samples of your work and then wait. And then wait a bit more. Then perhaps send a chasing letter. And just keep at it. Eventually, if you have a degree of talent, somebody will spot it and you'll get in print.

But don't stop there! It is a misconception that once you have made it in print, it gets easier. Okay, perhaps it's not entirely false, but it's not that simple. I am constantly sending out samples to people who already know me, or I email them and follow them on social media just to stay in touch. Otherwise they forget about me and they use somebody else's art and I have to live on bread and water. Most of the samples I send out to new potential clients just vanish into some black hole somewhere. It's tiring, but you have to know how to network as well as how to draw. And you need patience.

If you could travel anywhere in time and space (with safe return guaranteed), what astronomical object or phenomenon would you like to observe in real life?

Difficult one, but probably the interacting binary stars that I studied for my PhD. These systems are so compact (the entire system could fit inside the Sun) that it's doubtful we will ever have close-up photographs of them, no matter how powerful our telescopes become. I'd also love to just stand on the Moon at look back at Earth. From the Moon, the Earth appears four times larger in the sky than the Moon does from the Earth, and dozens of times brighter. And on the Moon the Earth never sets. It just hovers in the sky, cycling through its phases. That would be an awesome sight.