1st January 2013 As climate warms, bark beetles march on high-elevation forests Trees and insects wage constant war on each other. Insects burrow and munch on bark; trees deploy lethal and disruptive defences in the form of chemicals. But in a rapidly warming world, where temperatures and seasonal change are in flux, the tide of battle may be shifting in some insects' favour, according to a new study.

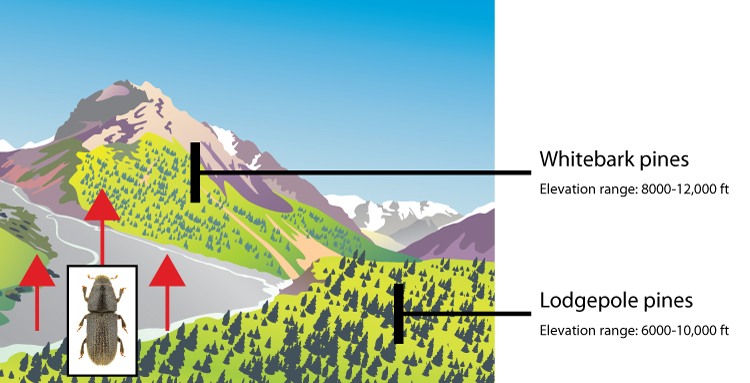

In a report published yesterday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a team of scientists from the University of Wisconsin-Madison reports a rising threat to whitebark pine forests in the northern Rocky Mountains as native mountain pine beetles climb ever higher, attacking trees that have not evolved strong defences to stop them. The whitebark pine forests of the western United States and Canada are the forest ecosystems that occur at the highest elevation to sustain trees. It is a critical habitat for iconic species such as the grizzly bear and plays an important role in governing the hydrology of the mountain west by shading snow and regulating the flow of meltwater. "Warming temperatures have allowed tree-killing beetles to thrive in areas that were historically too cold for them most years," explains Ken Raffa, a UW-Madison professor of entomology and a senior author of the new report. "Tree species at these high elevations never evolved strong defences." A warming world has not only made it easier for the mountain pine beetle to invade new and defenceless ecosystems, but also to better withstand winter weather that is milder and erupt in large outbreaks capable of killing entire stands of trees, no matter their composition.

"A subject of much concern in the scientific community is the potential for cascading effects of whitebark pine loss on mountain ecosystems," says Phil Townsend, professor of forest ecology and also a senior author of the study. The beetle's historic host is the lodgepole pine – a tree common at lower elevations. Normally, the insects, which are about the size of a grain of rice, play a key role in regulating the health of a forest by attacking old or weakened trees and fostering the development of a younger forest. However, recent years have been characterised by unusually hot and dry summers and mild winters, which have allowed insect populations to boom. This has led to an infestation of mountain pine beetles at higher elevations, described as the most significant insect blight ever seen in North America. In 2011, a similar study by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service found that whitebark pine forests could be extinct in 120 years, if trends continue. This would have major implications for the ability of Earth's biosphere to absorb and remove greenhouse gases (CO2) from the atmosphere.

Lodgepole pines (unlike whitebark pines) co-evolved with bark beetles at lower elevations. Over time, they devised countermeasures such as volatile toxic compounds and agents that disrupt the beetle's chemical communication system. Despite its strong defences, the lodgepole pine is still the preferred menu item for the mountain pine beetle, suggesting that the beetle has not yet adjusted its host preference to whitebark pines. "Nevertheless, at elevations consisting of pure whitebark pine, the mountain pine beetle readily attacks it," says Townsend. The study, conducted in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem – one of the last nearly intact ecosystems in the Earth's northern temperate regions – also revealed that insects preying on or competing with mountain pine beetles are staying in their preferred lodgepole pine habitat. That, says Townsend, is a concern because tree-killing bark beetles will encounter fewer of these enemies in fragile, high-elevation stands. Whitebark pines are a vital food source for wildlife, including black and grizzly bears, and birds such as Clark's nutcracker which is essential to the forest ecology as the bird's seed caches help regenerate the forests. With their broad crowns, high-elevation whitebark pines also act as snow fences, helping to slowly release water into mountain streams and extending stream flow into mountain valleys well into the summer. "Loss of the canopy will lead to greater desiccation during the winter and faster melting in the summer – due to loss of tree canopies for shade," says Townsend.

In a separate study last month, the U.S. Geological Survey reported that climate change is already having major effects on ecosystems and species. Plants and animals are shifting their geographic ranges and the timing of their life events – such as flowering, laying eggs or migrating – at faster rates than documented even just a few years ago. Mismatches in availability and timing of natural resources can influence species' survival. For example, if insects emerge before the arrival of migrating birds that rely on them for food, it can adversely affect bird populations. Species that must live at high altitudes or live in cold water within a narrow temperature range – such as salmon – face even greater risks. Earlier thaw and shorter winters can extend growing seasons for pests. This can substantially alter the benefits that humans derive from ecosystems, such as clean water, wood products and food.

Comments »

|