16th April 2020 Earth-sized exoplanet found in habitable zone NASA reports the discovery of an exoplanet that is closer to Earth in size and temperature than any other world yet found in data from the Kepler space telescope.

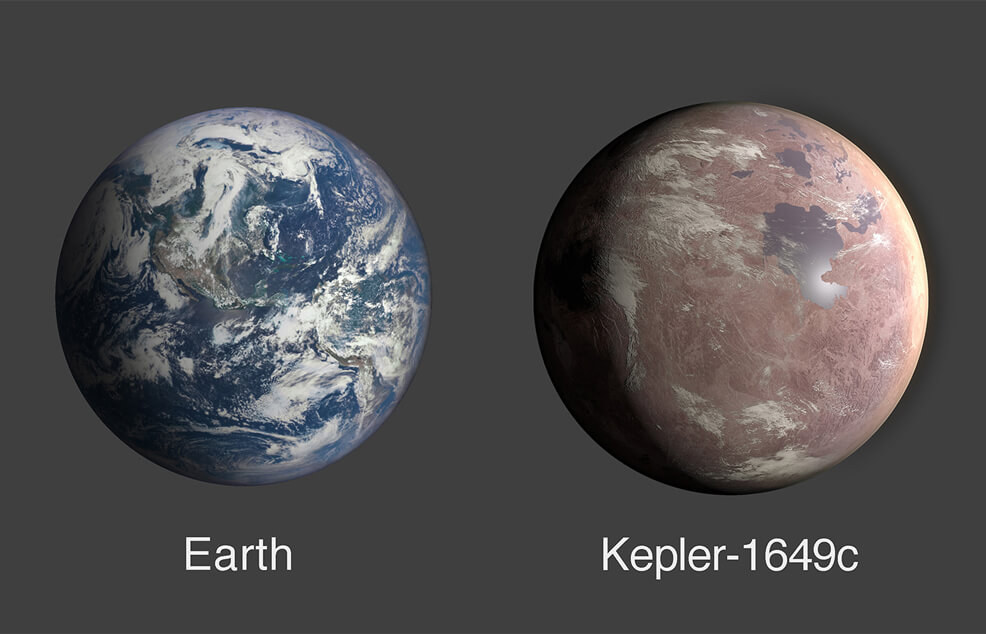

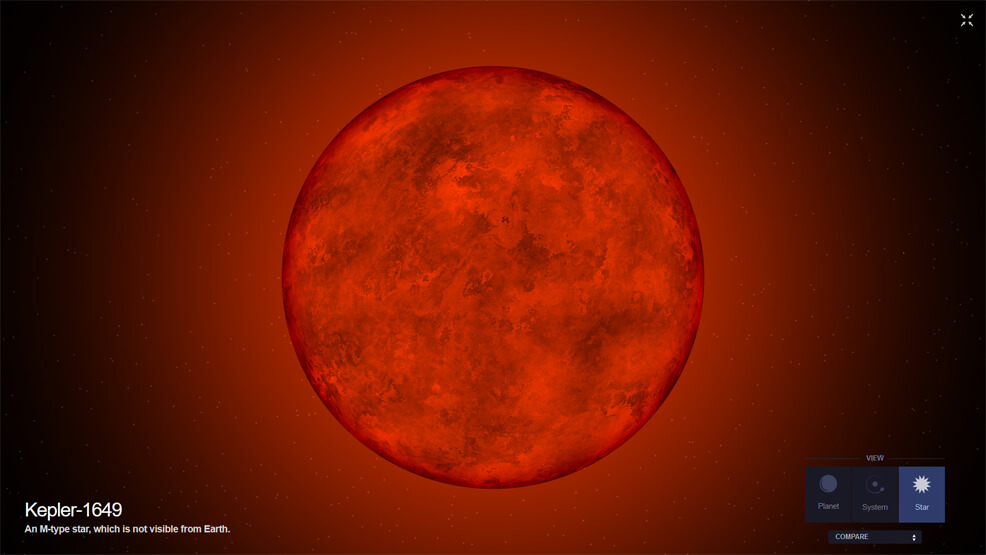

Using reanalysed data from Kepler, astronomers have calculated that Kepler-1649c is almost exactly the same size as Earth – at only 1.06 times larger than our home planet – and orbits in its star's habitable zone, where liquid water could exist on its surface. The agency retired Kepler in October 2018, but scientists continue to pore over the treasure trove of discoveries it made after observing 530,000 stars and confirming the presence of more than 2,300 planets. Thousands more candidates await confirmation. This new world, Kepler-1649c, is 301 light-years away and orbits an M-type star (pictured below) about one-fourth the size of our Sun. It shares the system with a second planet – Kepler-1649b – a larger and hotter world orbiting closer to the star, producing Venus-like conditions. Kepler-1649b circles around the red dwarf every 8.7 Earth days, while its smaller brother does so every 19.5 days. While the orbit is much shorter than the 365 days we experience here on Earth, a lower heat output from its parent star means that Kepler-1649c lies in a temperature range that could allow water on its surface. The team looked for evidence of a third planet, with no results. However, that could be because the planet is too small to see, or at an orbital tilt that makes it impossible to find using Kepler's transit method. Perhaps future telescopes could reveal this.

There is still much that is unknown about Kepler-1649c, including its atmosphere, which could affect the planet's temperature. Current calculations have significant margins of error, as do all values in astronomy when studying objects so far away. But based on what is known, Kepler-1649c is the most similar planet to Earth in terms of size and likely temperature that has ever been found with Kepler. A paper with more details is published this month in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. In their abstract, the authors write:

Previously, scientists on the Kepler mission developed an algorithm called Robovetter to help sort through the massive amounts of data. The Kepler telescope identified planets using the transit method, looking for dips in brightness as planets passed in front of their host stars. Most of the time, dips come from phenomena other than planets – ranging from natural changes in a star's brightness, to other cosmic objects passing by. Robovetter's job was to distinguish the 12% of dips that were real planets from the rest. Those signatures the algorithm determined to be from other sources were labelled "false positives," the term for a test result mistakenly classified as positive. With a vast number of complex signals, the researchers knew their algorithm would inevitably make mistakes and need to be double-checked – a task for the Kepler False Positive Working Group. That team reviews Robovetter's work, going through each false positive in meticulous detail, ensuring they are truly errors and not exoplanets – meaning fewer potential discoveries are overlooked. As it turns out, Robovetter had mislabelled Kepler-1649c. "Out of all the mislabelled planets we've recovered, this one's particularly exciting," said Andrew Vanderburg, a researcher at the University of Texas at Austin and first author on the paper. "If we hadn't looked over the algorithm's work by hand, we would have missed it. The more data we get, the more signs we see pointing to the notion that potentially habitable and Earth-size exoplanets are common around these kinds of stars." "This intriguing, distant world gives us even greater hope that a second Earth lies among the stars, waiting to be found," said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator of NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington. "The data gathered by missions like Kepler and our Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite [TESS] will continue to yield amazing discoveries as the science community refines its abilities to look for promising planets year after year."

Click to enlarge

Comments »

If you enjoyed this article, please consider sharing it:

|