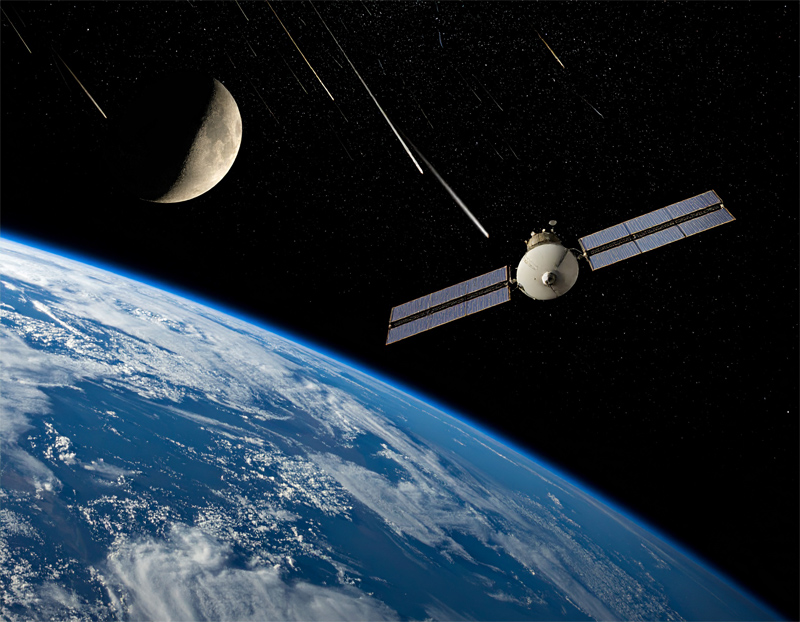

7th August 2025 Asteroid impact on Moon could threaten satellites in 2032 A new study has modelled the potential consequences of asteroid 2024 YR4 striking the Moon in 2032, finding that such an impact – if it occurs – would be the largest in 5,000 years, ejecting debris that could threaten satellites and produce a visible meteor shower on Earth.

A near-Earth object measuring 60 metres across has been capturing serious attention from astronomers. Although an impact on Earth can be ruled out, there is still a 4.3% chance of 2024 YR4 striking the Moon on 22nd December 2032. Based on the asteroid's mass and velocity, the impact would generate a blast equivalent to 6.5 megatons of TNT, forming a 1-kilometre crater and hurling vast amounts of lunar material into space. This wouldn't just be a geological event – it could have real implications for Earth and its satellites. A new paper by scientists at the University of Western Ontario and Athabasca University investigates the likely effects of such a collision. Their findings suggest that up to 100 million kilograms of debris could be ejected at speeds exceeding lunar escape velocity. This high volume of escaping debris is made possible in part by the Moon's low gravity – just one-sixth that of Earth – which allows material to launch into space more easily than it would from our planet. While most of this material would continue drifting through space, a significant portion could head straight for Earth, arriving within a few days of the impact. Delivery of debris to Earth depends heavily on the exact location of a Moon strike. If the asteroid were to hit the trailing side of the Moon – the side opposite the direction of its orbit – debris would stand a higher chance of reaching our planet quickly. Simulated impact scenarios show that up to 12% of escaping material could rain down on Earth, arriving within a week of the collision. This would generate a meteor shower visible from the ground, but more worryingly, it would also pose a serious risk to satellites in orbit.

The impact would likely occur on the near side of the Moon – the side visible from Earth. In such a scenario, a bright flash could light up the lunar surface for several seconds, potentially visible to the naked eye. It would be a once-in-a-lifetime spectacle. But the aftermath could be more sobering. Satellites in low Earth orbit (LEO) are particularly vulnerable. Ejecta particles between 0.1 and 10 millimetres in diameter – while tiny – can cause damage due to their high speeds. The study estimates that satellites could experience the equivalent of several years to a decade's worth of background meteoroid impacts, compressed into a matter of days. For large constellations like Starlink, this translates to hundreds or even thousands of additional impacts across the fleet. Though most of these wouldn't end missions outright, they could degrade the performance of spacecraft, increase failure rates, or generate more space debris through fragmentation. Delicate components like solar panels could take the brunt of damage, akin to gravel cracking a car windshield at high speed. The event is unlikely to trigger a Kessler Syndrome-style cascade of destruction, but could still cause serious disruption to services like GPS, telecommunications, and Earth monitoring. Even a partial loss of access to space infrastructure could pose a serious risk to humanity. The threat isn't limited to LEO. Debris could linger in higher orbits for months or even years, affecting many other spacecraft – particularly those with delicate parts or limited shielding. Operations on and around the Moon – such as the planned Lunar Gateway – could also face elevated risks. With no atmosphere to slow or absorb flying material, the Moon would see debris spread far and fast across its surface, potentially endangering astronauts or research habitats.

Interestingly, Earth's atmosphere would filter out most of the smaller particles, turning them into harmless meteors. The influx of this material would far exceed the typical daily input of space dust, likely resulting in a spectacular meteor shower. However, the slower entry speeds of lunar ejecta mean these meteors would appear less bright than typical shooting stars. Despite its small size, YR4 has already made a big impact in scientific circles. Initially discovered by the ATLAS telescope in Chile, it wasn't spotted until after it had already passed closest to Earth, hidden by the Sun's glare. At one point it had the highest known probability of hitting our planet – peaking at 3.1% in February 2025. Follow-up observations by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) in March and May helped refine its orbit and eliminated the risk to Earth. However, those same observations slightly increased the chance of a lunar impact. The JWST played a crucial role in tracking YR4 for longer than any ground-based telescope could. In fact, it remains the only telescope capable of detecting the asteroid again before 2028. Astronomers plan to use a newly approved observing programme in 2026 to update its position, helping decision-makers to prepare – or more likely, relax – ahead of the 2032 date. For planetary defence experts, YR4 serves as a wake-up call. Until recently, most efforts focused on asteroids threatening Earth. But as lunar activity ramps up and more satellites populate cislunar space, scientists argue that we must expand our definition of what counts as a threat. As Dr Paul Wiegert, lead author of the new paper, puts it: "We're starting to realise that maybe we need to extend that shield a little bit further. We now have things worth protecting that are a bit further away from Earth, so our vision is hopefully expanding a little bit to encompass that." Whether or not YR4 ultimately strikes the Moon, the episode highlights the growing complexity of space safety. It also reinforces the importance of missions like NASA's NEO Surveyor and ESA's NEOMIR, which aim to close the Sun-facing blind spot in our asteroid detection network. If YR4 does hit the Moon, it would present a unique scientific opportunity. For the first time in modern history, astronomers could observe a "city killer"-scale impact as it happens. Studying the lunar surface response would give researchers vital data to improve crater modelling, understand dust dynamics, and enhance shielding for future habitats. Asteroid 2024 YR4 may turn out to be nothing more than a cosmic near-miss. But its story highlights just how much remains unknown – and how much we still need to learn to keep space safe. With better monitoring, smarter planning, and growing international cooperation, we can turn even potential threats like this into opportunities for progress.

Comments »

If you enjoyed this article, please consider sharing it:

|

||||||