12th December 2025 Somatic mutations may set a hard limit on human longevity New research suggests that even if we cured almost every aspect of aging, humans might still struggle to live beyond about 150 years, due to the slow and unavoidable accumulation of random DNA errors in our cells.

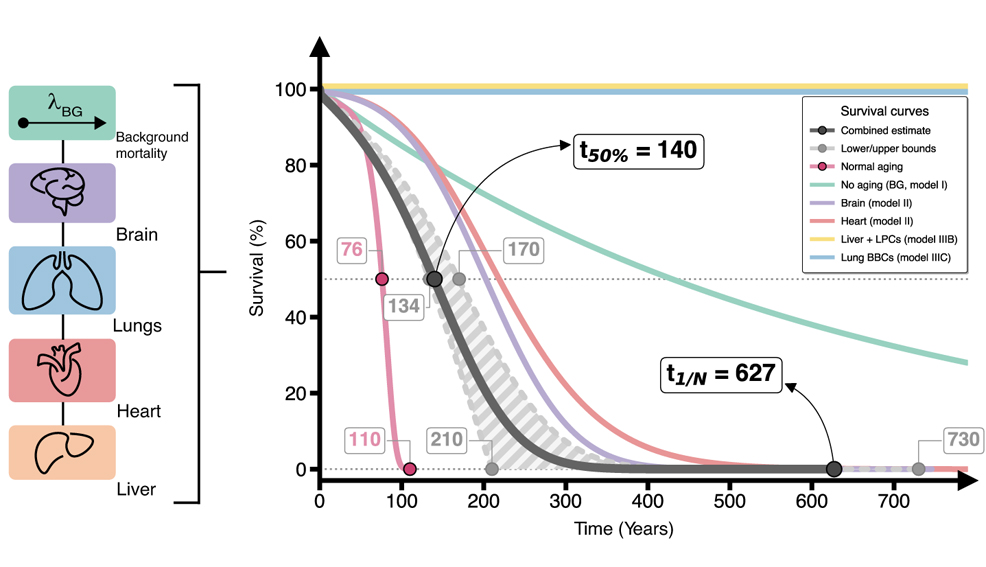

How long could humans live in a future where medicine reverses most biological aging? Some scientists imagine lifespans of centuries or even millennia. But a new modelling study offers a more grounded, physics-based answer. It suggests that one fundamental process would remain, no matter how advanced our therapies become: the gradual build-up of random mutations in the DNA of our cells. These mutations are tiny errors that appear throughout life. Many are repaired or eliminated, but over decades some inevitably persist. In aging research, this gradual accumulation of genetic errors is sometimes described as an entropic process, reflecting the tendency of living systems to drift toward increasing molecular disorder. The scientists behind the study, which appears on the preprint server bioRxiv and has not yet been peer reviewed, set out to isolate this single process and ask a deceptively simple question: if we fixed everything else, how long could humans live with somatic mutations as the only cause of aging? Somatic mutations occur in the body's ordinary cells, rather than in reproductive cells such as sperm or eggs, and so influence the individual but not future generations. To answer this question, they built a detailed mathematical model of four major organs: the brain, heart, liver, and lungs. Each organ behaves differently as it ages, so the team modelled their cell populations one by one, then combined them into a complete picture of human survival. The study found a striking imbalance between two categories of tissues. Some parts of the body can easily regenerate and replace damaged cells. Others cannot. The liver, for example, is extremely resilient. Its cells can replicate many times, and a small pool of stem cells helps replenish damaged tissue. According to the researchers' model, a healthy liver might remain functional not just for centuries but for tens of thousands of years. In other words, somatic mutations alone would barely affect it. The lungs also showed much more resistance than expected. Their airway stem cells gradually lose the ability to divide and eventually fail, but the model suggests this would take several thousand years. Again, not a limiting factor for human longevity.

The real weak points are the organs that cannot regenerate: the brain and the heart. Neurons and cardiomyocytes are largely fixed for life. When enough of them accumulate lethal mutations, they die, and the organ slowly loses function. Because these cells cannot easily be replaced, the damage compounds. The model estimated that the brain would fail after 730 years, and the heart after 1,236 years, if mutation accumulation were the only aging process. These numbers might sound large, but the study also factors in a constant "background risk" of death (roughly equivalent to a healthy 30-year-old's level) from accidents, infections, and other non-aging causes. When this everyday mortality is combined with slow organ failure, the result is a surprisingly strict limit on how long most people could ever live. After combining all four organs into a single model, the authors found that in a world where all other hallmarks of aging were cured, the median human lifespan would be around 134 to 170 years. The absolute upper limit is likely somewhere between 210 and 730 years. This is far beyond the current record of 122 years, yet far short of the near-immortality sometimes discussed in speculative circles. In simple terms, curing most forms of aging would probably only double your life expectancy, unless we also find ways to replace or rejuvenate non-dividing cells in the brain and heart. The study also emphasises what the model cannot explain. If somatic mutations were the dominant driver of aging today, humans should already be living closer to 150 years. The fact that we do not means other aging mechanisms contribute at least as much. These include mitochondrial decline, epigenetic deterioration, inflammation, and the accumulation of senescent cells. Somatic mutations are important, but they are only one piece of a much larger puzzle. Nevertheless, the study provides a useful boundary for thinking about the future of longevity science – assuming no routine organ replacement, and excluding more speculative ideas such as mind uploading or digital consciousness. It shows that genuine life extension beyond 150 years will almost certainly require some major breakthroughs in neural and cardiac cell replacement. Stem cell therapies, engineered tissues, or advanced gene editing may eventually shift these limits. Until then, somatic mutation represents a fundamental entropic barrier that no medicine can yet cross.

Comments »

If you enjoyed this article, please consider sharing it:

|

||||||