17th December 2025 New record for smallest fully autonomous robot Researchers in the US have created the world's smallest fully programmable, autonomous robots, measuring just 200 x 300 x 50 micrometres.

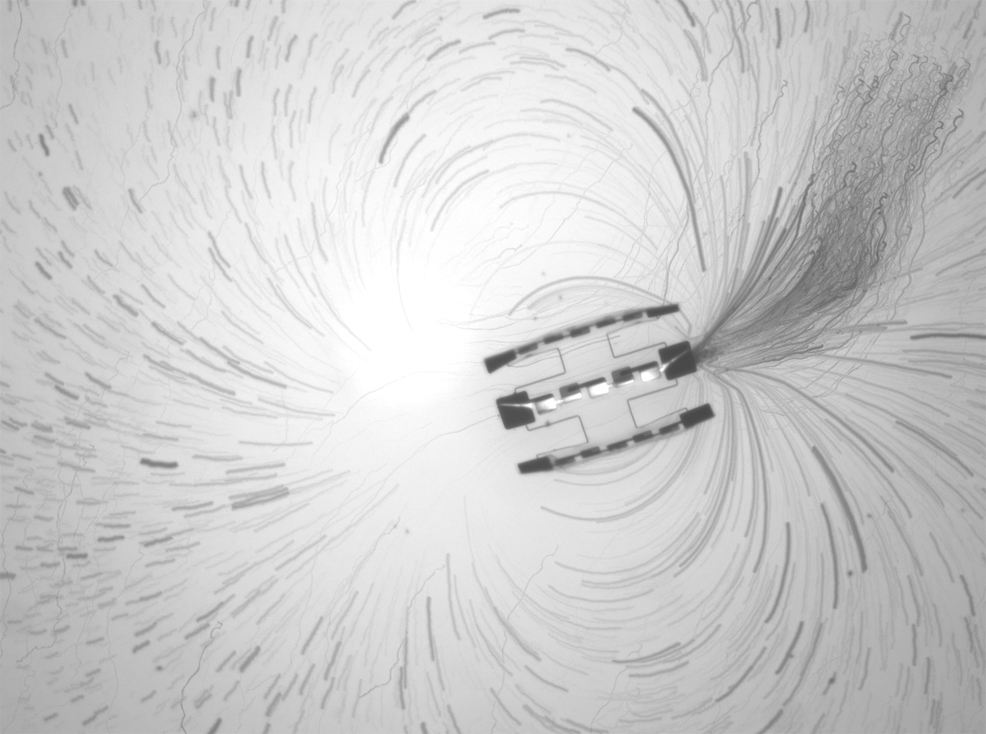

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Michigan have unveiled what they describe as the world's smallest fully programmable, autonomous robots. Barely visible to the naked eye and small enough to balance on the ridge of a fingerprint, they can independently sense their surroundings, make decisions, and move through liquid environments – all while operating for months and costing just a penny each. Measuring 200 by 300 by 50 micrometres, the robots operate at a scale comparable to many biological microorganisms. Their creators suggest this could open up new possibilities in medicine, such as monitoring the health of individual cells, as well as in manufacturing, where they could help assemble microscale devices. The robots are powered by light and carry microscopic computers that allow them to execute preloaded programmes. They can move in complex patterns, sense local temperatures and adjust their behaviour accordingly. Crucially, they operate without any tethers, magnetic fields or external control, making them the first truly autonomous and programmable robots at this scale. The work is described in Science Robotics and Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. "We've made autonomous robots 10,000 times smaller," says Marc Miskin, Assistant Professor in Electrical and Systems Engineering at Penn Engineering and senior author on the papers. "That opens up an entirely new scale for programmable robots." For decades, robotics has struggled to shrink in the same way electronics has. "Building robots that operate independently at sizes below one millimetre is incredibly difficult," says Miskin. "The field has essentially been stuck on this problem for 40 years." At microscopic scales, the familiar forces that govern everyday motion give way to drag and viscosity. "If you're small enough, pushing on water is like pushing through tar," he explains. Instead of relying on tiny moving limbs, which are fragile and hard to manufacture, the team developed a propulsion system that works with microscale physics. The robots generate electrical fields that nudge ions in the surrounding solution. These ions, in turn, push nearby water molecules, creating motion. "It's as if the robot is in a moving river," says Miskin, "but the robot is also causing the river to move."

This approach allows the machines to travel at speeds of up to one body length per second, manoeuvre in complex paths and even move collectively, like a school of fish. With no moving parts, the propulsion system is also highly robust. "You can repeatedly transfer these robots from one sample to another using a micropipette without damaging them," says Miskin. Charged by LED light, they can keep swimming for months. Autonomy at this scale required equally radical advances in electronics. The challenge was addressed by a team led by David Blaauw at the University of Michigan whose lab already holds the record for the world's smallest computer. When the two groups first met at a DARPA event five years ago, the potential collaboration was immediately clear. "We saw that Penn Engineering's propulsion system and our tiny electronic computers were just made for each other," says Blaauw. Power was the main constraint. "The solar panels are tiny and produce only 75 nanowatts of power," Blaauw explains, "over 100,000 times less power than what a smart watch consumes." To overcome this, the team designed ultra-low-voltage circuits and radically compressed the robot's software. "We had to totally rethink the computer program instructions," he says, condensing what would normally require many instructions into a single custom command. The result is the first sub-millimetre robot to include a true computer, complete with processor, memory and sensors. The robots can detect temperature changes to within a third of a degree Celsius and respond autonomously. To communicate their readings, they perform distinctive motion patterns that researchers can decode under a microscope. "It's very similar to how honey bees communicate with each other," says Blaauw. Beyond the immediate technical achievement, the work highlights a broader trend in miniaturisation. Over the last decade or so, the volume of autonomous or semi-autonomous devices has been falling by orders of magnitude. Now at just 0.003 cubic millimetres, these robots could soon be invisible to human eyes. Assuming the current rate of shrinkage continues, fully autonomous machines comparable in size to red blood cells may be achievable in the 2040s or sooner, blurring the line between engineered systems and living organisms. For now, the researchers see their creation as a platform rather than a finished product. "This is really just the first chapter," says Miskin. "We've shown that you can put a brain, a sensor and a motor into something almost too small to see, and have it survive and work for months. Once you have that foundation, you can layer on all kinds of intelligence and functionality."

Comments »

If you enjoyed this article, please consider sharing it:

|

||||||