13th January 2026 The first global timeline of Earth's vanishing glaciers Scientists have unveiled the first global timeline of glacier loss, warning that the Alps may reach peak glacier loss as early as 2033, while tens of thousands of glaciers worldwide are projected to vanish this century.

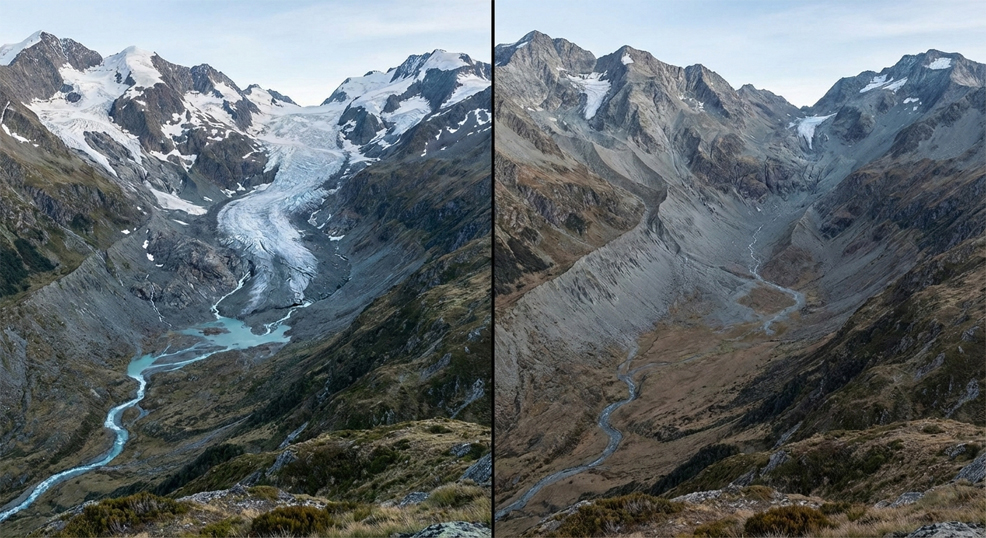

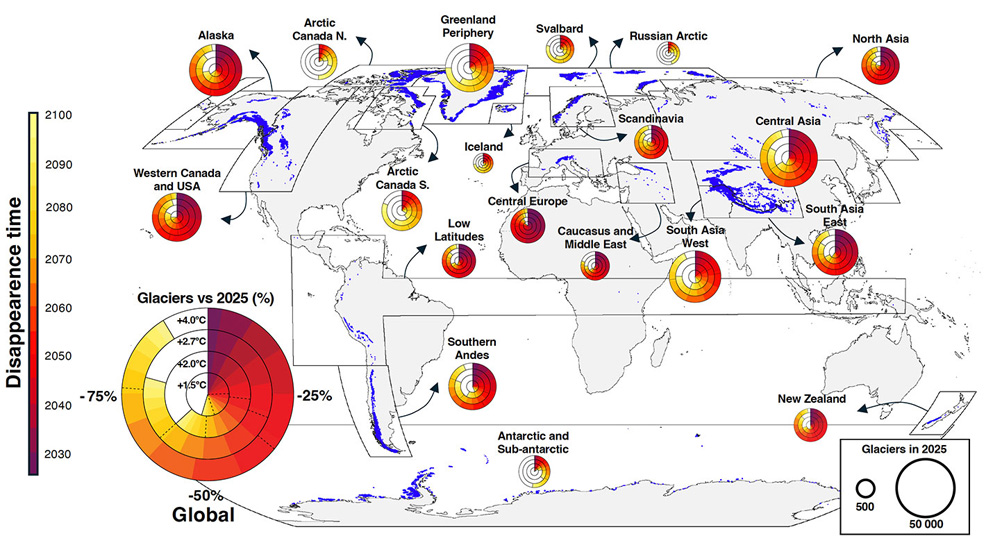

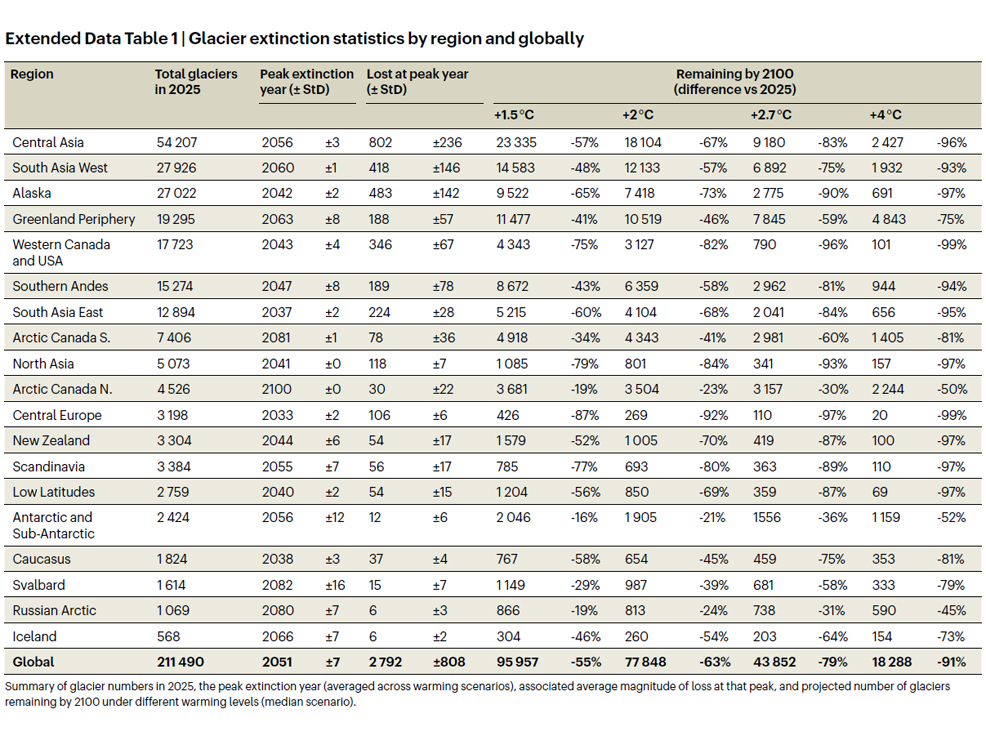

Until relatively recently, most people treated glaciers like permanent features of the landscape. Mountain railways, tourist viewpoints and school textbooks presented them as slow-moving but enduring bodies of ice. However, a new study published in Nature Climate Change overturns this now outdated perception by introducing a striking new metric for understanding ice loss. The researchers define a moment they call "Peak Glacier Extinction" – the point at which the number of glaciers disappearing each year reaches its maximum before inevitably declining as fewer glaciers remain. An international team led by ETH Zurich developed this concept by shifting attention away from ice mass alone and towards the survival of individual glaciers. Rather than asking how much ice the planet loses, the study asks a simpler and more tangible question: when does each glacier cease to exist as a glacier at all? The researchers addressed this by analysing 211,000 glaciers worldwide using three global glacier models and several warming scenarios extending to 2100. Rather than simulating each glacier in fine detail, the team combined the existing global glacier catalogue with three well-established glacier evolution models, which estimate how glacier area and volume respond to changing climate conditions over time. By applying the same physical rules to every glacier under multiple warming scenarios, the researchers could track when each glacier shrinks below a minimum threshold (either less than 0.01 km² in area or less than 1% of its original volume) and effectively disappears. This approach made it possible to analyse such a vast number of glaciers in a consistent and comparable way. Peak Glacier Extinction marks the year when the number of glaciers disappearing each year reaches its maximum. Under a global temperature rise of 1.5 °C, broadly aligned with the Paris Agreement, the models place this peak around 2041, with roughly 2,000 glaciers disappearing in a single year. Under a 4.0 °C warming scenario, the peak shifts to 2055, but the scale of loss doubles, with around 4,000 glaciers vanishing annually. Today's modelled loss rate stands closer to 750–800 glaciers per year, highlighting how much worse conditions could become within just a few decades. The Alps emerge as one of the most vulnerable regions on Earth. Because they contain thousands of small, low-elevation glaciers, they respond rapidly to rising temperatures. In Central Europe, the study projects Peak Glacier Extinction as early as 2033, meaning the coming decade could see the highest annual rate of glacier disappearance ever recorded in the Alps. "In these regions, more than half of all glaciers are expected to vanish within the next ten to twenty years," says Dr. Lander Van Tricht, lead author and a researcher at ETH Zurich.

Credit: Basemap / Natural Earth / Springer Nature / ETH Zurich, Chair of Glaciology

By 2100, the numbers collapse dramatically under every warming pathway. From around 3,200 glaciers today, the Alps retain just 430 even under a 1.5 °C rise, roughly 270 under 2.0 °C, around 110 under 2.7 °C, and only 20 under 4.0 °C. That last scenario represents the loss of roughly 99% of Alpine glaciers. Elsewhere, the picture looks similarly stark. Out of 211,000 glaciers worldwide in 2025, the study projects that 96,000 survive by 2100 under 1.5 °C of warming, a loss of 55%. At 2.7 °C, that figure drops to about 44,000, while at 4.0 °C only 18,000 glaciers remain. Regions dominated by small glaciers, including parts of the Andes, the Caucasus, the Rocky Mountains and several African mountain ranges, experience especially rapid losses. Even the Karakoram, one of the few regions where some glaciers temporarily advanced in the early 2000s, shows a clear long-term decline in glacier numbers. Dr. Van Tricht describes the work as a change in perspective. "For the first time, we have put years on when every single glacier on Earth will disappear," he said. By assigning timelines in this way, the study reveals how sensitive outcomes are to even small differences in warming. Under higher temperatures, not only do small glaciers vanish more quickly, but larger and more resilient glaciers also begin to disappear entirely.

Counting glaciers rather than tonnes of ice also sharpens the economic and cultural implications of ice loss. While the disappearance of a small glacier adds little to global sea-level rise, it can carry outsized local consequences. Glaciers attract millions of visitors each year and underpin tourism economies across many mountain regions. Their loss can reduce visitor numbers, threaten ski resorts that rely on glacier ice, and alter the character of valleys that built their identities around iconic ice features. As Van Tricht notes, when a glacier disappears completely, it can severely affect tourism in a valley. Glaciers also function as natural water reservoirs, releasing meltwater during warm and dry periods. As they shrink and vanish, downstream regions may face more variable water supplies and changing natural hazard risks. The timing of glacier loss therefore matters as much as the total amount of ice lost. A world approaching Peak Glacier Extinction is one in which many communities lose critical environmental buffers within a single generation. The term itself carries an uncomfortable irony. After Peak Glacier Extinction, the annual number of disappearing glaciers falls, but only because so many have already vanished. "The results underline how urgently ambitious climate action is needed," said Daniel Farinotti, study co-author and a Professor of Glaciology at ETH Zurich. Every fraction of a degree Celsius of warming alters how many glaciers survive into the next century, and how quickly the world reaches the point of greatest loss.

Comments »

If you enjoyed this article, please consider sharing it:

|

||||||