16th January 2026 Human brain-scale simulations move a step closer Researchers have developed a new GPU-based method for constructing large neural networks, making the setup phase over ten times faster and paving the way for human brain-scale simulations on future supercomputers.

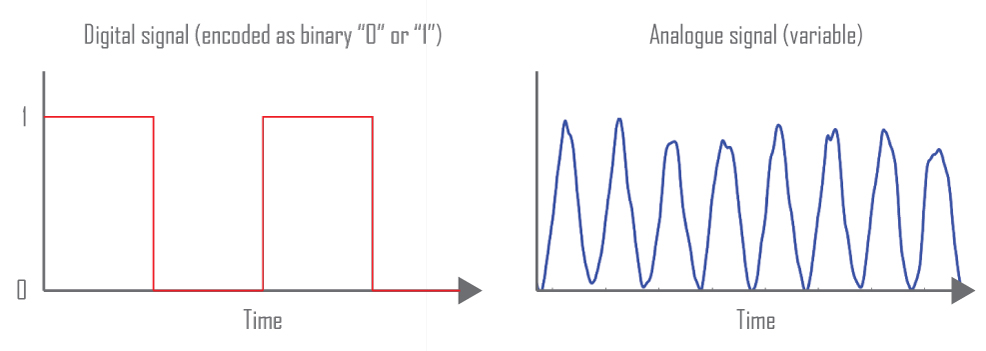

Simulating the brain at the level of individual neurons and synapses represents one of the most demanding challenges in computational science. Even a tiny square millimetre of cerebral cortex can generate more than a billion synaptic events per second, as millions of neurons exchange brief electrical spikes with millisecond precision. A new study by an international research team describes a significant advance in tackling this problem, by radically speeding up how such enormous neural networks are built and prepared for simulation on modern supercomputers. The work has been carried out by a team at the University of Cagliari and Italy's National Institute for Nuclear Physics, together with collaborators at the Jülich Research Centre and RWTH Aachen University in Germany, as well as the University of Sussex in the UK. Their work involves spiking neural networks, a type of computer model able to closely mimic the brief electrical pulses used by real neurons to communicate in the brain. These models play a central role in computational neuroscience and increasingly influence neuromorphic and brain-inspired AI research. Unlike traditional AI models that use constant digital numbers (like binary 0s and 1s flowing steadily), spiking neural networks behave much more like the brain's analogue signals – short, variable electrical spikes that carry information through their precise timing. This makes them far more efficient for mimicking real brain activity on specialised neuromorphic hardware. But until now, building large-scale versions has been a huge computational challenge.

Digital versus analogue signalling: traditional AI models compared with more realistic "spiking" neural networks.

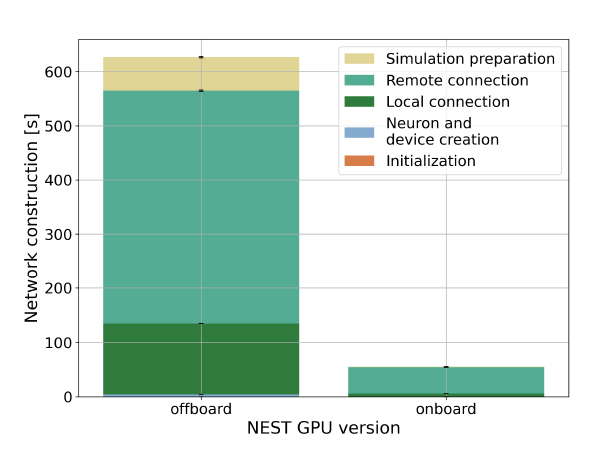

In large-scale simulations, the challenge is more than just running the model forward in time. Before any biological activity can be simulated, the software must construct the entire network, defining every neuron, every synapse, and every pathway along which spikes travel between graphics processing units (GPUs) – specialised chips designed for parallel computation. For highly realistic brain models, this setup phase can dominate the total runtime on clusters of GPUs. Researchers often need to rebuild networks repeatedly when tuning parameters, testing hypotheses, or running groups of simulations. In that context, a setup measured in tens of minutes or hours per run quickly adds up to a severe productivity bottleneck, even on the world's fastest machines. For this study, the researchers addressed this bottleneck by rethinking how large neural networks are constructed. In earlier "offboard" approaches, much of the setup work took place on the central processing unit (CPU) of a computer before being transferred to the GPU, creating delays and forcing repeated data shuffling back and forth between processors. The new "onboard" method skips this step entirely, allowing each separate GPU to build its own local part of the brain network directly within its own memory, without waiting for other GPUs or routing large data structures through the CPU. To manage communication later on, the system includes lookup tables (essentially organised address books that quickly match "which neuron talks to which"). These guide the flow of spikes during the simulation itself, while avoiding costly coordination during the setup phase. The result is a more than ten-fold reduction in network setup time – from nearly 12 minutes down to just 55 seconds. The change can be likened to organising a vast library. Instead of sending every book to one central desk to be catalogued and then shipped back out, each room in the library can organise its own shelves and keep a local index of where every title lives. A set of shared address books then tells you instantly which room to go to when you need a particular book, turning a once slow task into a quick and efficient process. The researchers tested this approach on a realistic model of 32 vision-related areas in the macaque monkey cortex, comprising 4.1 million neurons and 24 billion synapses spread across 32 NVIDIA GPUs. Most of the improvement comes from building local connections 20 times faster and remote connections 9 times faster, while producing identical neural activity to the previous method. The graph below shows how this new "onboard" approach cuts time across every stage of the neural network construction.

Looking ahead, the authors say their method is scalable to far larger and more ambitious models. They point to Europe's first exascale supercomputer, JUPITER, which recently began operations, featuring powerful GH200-class GPU nodes and ultra-fast interconnects that move data between processors with minimal delay. On systems of this scale, the same approach could support simulations of 20 billion neurons and on the order of 10¹⁴ synapses, equivalent to the full human cerebral cortex, while still tracking individual connections and millisecond-level spikes. Reaching this level of detail would transform what brain simulations can be used for. Instead of relying on simplified or abstract models, researchers could start combining ideas that were previously tested only in isolation. "We have never been able to bring them all together into one place, into one larger brain model where we can check whether these ideas are at all consistent," says co-author Markus Diesmann, a computational neuroscientist at the Jülich Research Centre, which hosts JUPITER. "This is now changing." In practical terms, full-scale simulations could help scientists explore how memories form and fade, how learning reshapes neural circuits over time, and why certain patterns of activity lead to disorders such as epilepsy. They could also serve as early testing grounds for new medicines, allowing researchers to observe brain-wide effects before moving to laboratory or clinical studies. While such models may never be perfect replicas of real brains, this work marks an important step forward. By turning brain-scale simulation from a distant aspiration into a realistic engineering problem, the study brings neuroscience and supercomputing closer than ever to explaining how thought, learning and behaviour emerge from billions of interacting neurons.

Comments »

If you enjoyed this article, please consider sharing it:

|

||||||